Revisiting an "Unsung Hero"

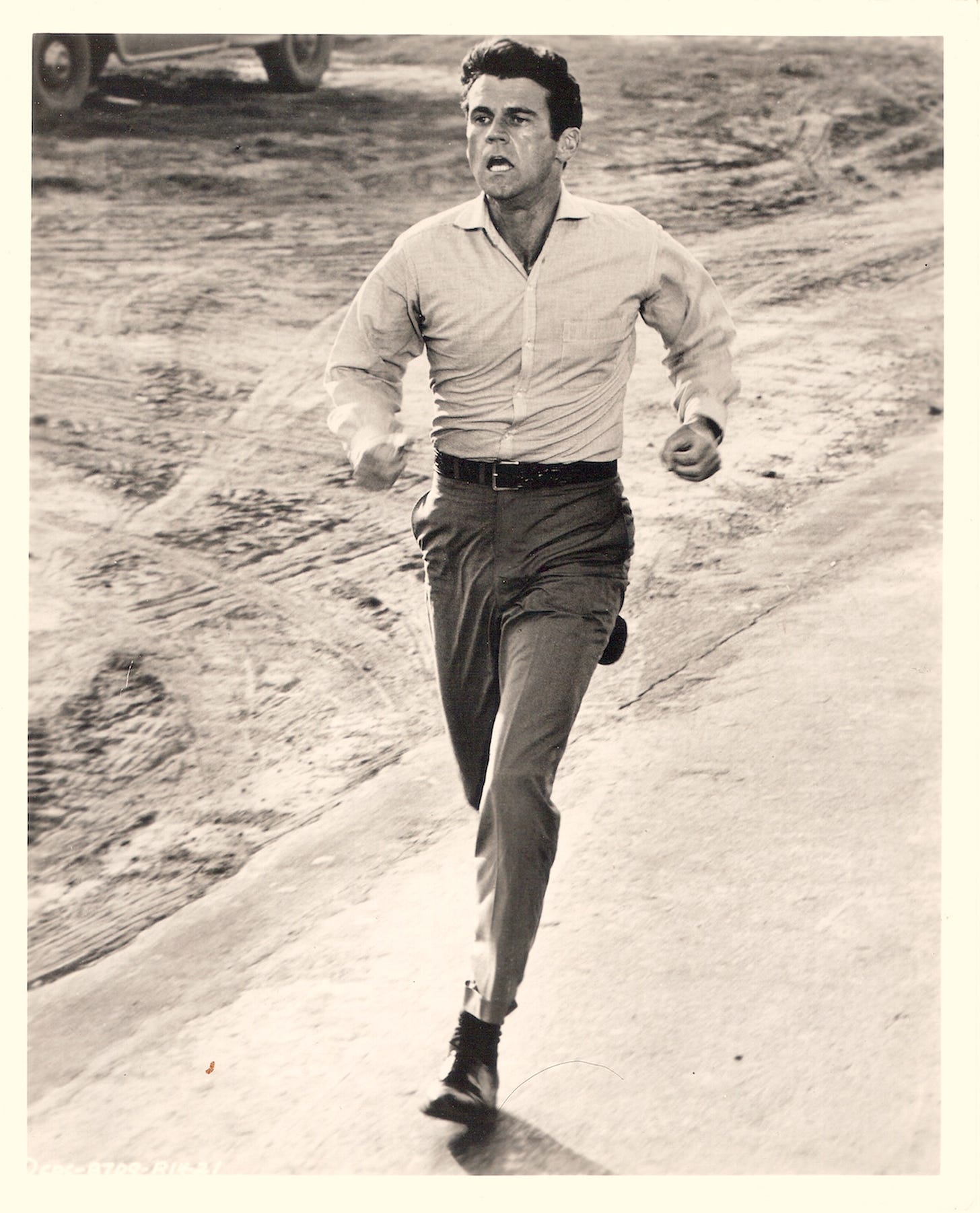

EXCAVATING SHARDS FROM THE OVERACTIVE, UNDERSEEN CAREER OF DON MURRAY

Don Murray turns 93 on July 31st, and he remains an unsung hero. Best known for BUS STOP, a film that mostly obscures his palpable need to play characters who marinate themselves in contradiction, his quiet, principled attempt to make films that occupied a category of his own invention—he called them “weapons of mass instruction”—has long been eclipsed by the “hot licks and rhetoric” of the Hollywood that he always distrusted.

With our modest pairing of films on his birthday, we hope to revisit some of the spirit that prevailed when he was a robust participant in a singular career retrospective held at the Roxie Theater in the summer of 2014.

A number of Don’s “problem films” surfaced in that series—from the strange Saul-to-Paul tale CHILDISH THINGS (later THE CONFESSIONS OF TOM HARRIS), with its oddball clash between the sacred and the profane, to the still-unreleased CALL ME BY MY RIGHTFUL NAME, an enigmatic love triangle wrapped inside the riddle of a despairing treatise on race relations. One of Murray’s business managers felt that he “made independent films designed to blow up his Hollywood career once and for all, so he could go back to the stage.”

A pacifist and a humanitarian at heart (as a teenager, his favorite actor was Lew Ayres), Don shined most in films where his character’s flaws were double-coated in denial: the self-loathing drug addict in A HATFUL OF RAIN; the Senator with sexual kryptonite in his past in ADVISE & CONSENT.

But he picked other roles where he could be convincingly clumsy as well—in CALL ME BY MY RIGHTFUL NAME, this is so foregrounded that some who’ve seen it (no mean feat!) felt that he’d regressed to a histrionically liminal state prior to acting school. But his intense desire to drive home the point that whites in America have (and still have) only the tiniest amount of understanding about the impact of racial prejudice in a nation still fractured by its slave-holding past compelled him to play characters who thought they really did understand—but didn’t.

This long-buried 1972 film was the second time that Don had played such a character; on Sunday we will bring you the first: SWEET LOVE, BITTER, a film maudit that survived a double butchering by its producers—twenty minutes cut from it, and a squalid title change for its initial release that prompted some folks to mistakenly think it was the new film from Doris Wishman. (You can see that title below, in the footnote…)1

Bleak, beautiful, and buoyed by a sensational Mal Waldron score, SWEET LOVE, BITTER (based on the novel Night Song by John Williams) tells the tale of Richie “Eagle” Stokes, a stand-in for Charlie Parker, whose life and career are spiraling downward. (The inimitable comedian Dick Gregory made an astonishing and impressive transformation in the role.) Equally bereft is David Hillary (Murray), an alcohol-impaired academic on an existential bender after accidentally causing his wife’s death. He and Stokes take up a strange bond, one that forces Stokes’ friend and keeper Keel Robinson (a tense, coiled Robert Hooks) to admit him into the real world of black affliction. Stokes, just like his real-life model, is in the throes of a heroin addiction.

The film operates as a measured but highly charged learning curve for Hillary, who begins to think he understands “what things are really like” as he manages to do what Stokes cannot: pull himself out of his existential despair. His illusions will be cruelly shattered just as he is about to be accepted back into the world of white privilege.

“The more you watch the film,” pre-eminent jazz critic Francis Davis noted, “the more it becomes clear just how much space as a cultural counter-argument against dominant society was inhabited by jazz. But the price paid to maintain that placement was not something that a well-meaning but dunderheaded white academic like David Hillary could grasp—unless he witnessed injustice and tragedy firsthand. Don Murray was one of the very few actors in the 60s who could walk the fine line to show how his character’s cultural sophistication was also his Achilles heel.”

Don’s performance is central to the strategy employed by director Herbert Danska to reshape Williams’ novel (rich almost to the point of clogging with psychological detail) for the big screen. Despite it being shorn of an extended phantasmagorical sequence where Eagle engages with a protégé whose fame has eclipsed his own (played by the masterful Carl Lee), SWEET LOVE, BITTER is a remarkable work that deserves to be restored to a honored place in the cycles of repertory cinema.

AS noted, Don Murray really did prefer the stage, but his first wife, Hope Lange, had aspirations to be a movie star, and so Hollywood beckoned. After his herculean success with BUS STOP, Don tossed back script after script to the top-knots at Fox, leading to an increasing tension between the studio and their stubbornly principled wonder boy. His self-sacrificing self-sabotage was mitigated (at least temporarily) by a phenomenon we can barely understand today: the desire of TV network executives to escape the stigma of their medium being called “a vast wasteland” by broadcasting plays by noted authors live over the airwaves.

The “golden age of live TV,” as it’s referred to whenever anyone bothers to remember it, was a fleeting comet across the cultural sky in the last half of the 1950s. It was made for Don Murray, who, like many stage actors who emigrated from New York, had pangs of remorse about abandoning what most of them felt was the true actor’s calling.

Beginning with his heartfelt portrayal of army deserter Axel Normand in “A Man is Ten Feet Tall” (opposite a young, preternaturally ebullient Sidney Poitier) and ending with his haunted boy-man Randy Bragg, who must grow up fast when nuclear holocaust hits America in Playhouse 90’s last great episode “Alas, Babylon”, Don found the middle ground between his invidious Hollywood obligations and the elegant bombast of stage acting in nearly a dozen adrenaline-pounding “one night only” events. When these disappeared, his lifeline to a mass audience was abruptly snapped. His career would suffer proportionately.

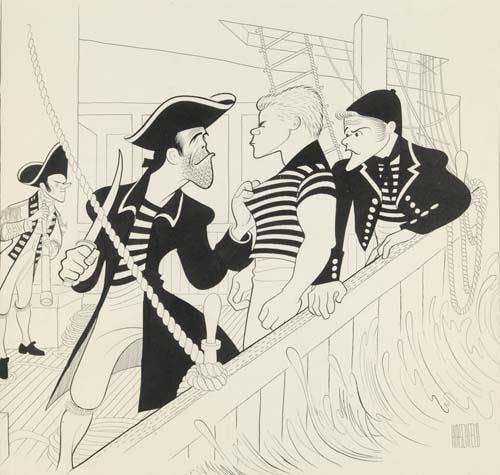

“Billy Budd” (broadcast as the “DuPont Show of the Month” in May 1959) is one of those impossibly hard-to-find artifacts of a strangely wondrous hybrid world, and a perfect example of the upscale aspirations of a coterie of TV executives who longed for a literary component to an otherwise threadbare medium. Director Robert Mulligan (most famed for TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD a few years later, but a prolific and highly accomplished live TV director) uses his three sets with great skill to add a cinematic quality to the proceedings, and gets spirited performances from all his principals, creating a work that has all the claustrophobic qualities that the 1962 film version mostly lacks.

Blond icing makes Murray into a quite credible Billy, not nearly so searingly silent as Terence Stamp but more than serviceable, placing him into a parallel region of the dunderheads he’d begin to perfect a few years later. He is aided by a superb performance from Alfred Ryder as Claggart, with all the homoerotic self-loathing that can possibly be displayed on a 10-inch screen. (Ryder, a last-minute substitute for Jason Robards, is menacing, pitiful, and haunted all at once; like no one else, he has captured the sinewy, sinuous prose that Herman Melville employed to reveal Claggart’s strangely pitiable monstrosity.)

We hope that more of Murray’s TV work can be unearthed, and possibly collected together for general release: of all the actors who spent significant time “putting on a play” in front of a live national TV audience, Don is the one who best captured that fleeting medium’s protean possibilities. It would be a great boost to our understanding of his career and its often careening motivations, and we would have an anchor with which to properly contextualize a man who deserves to shed the mournful label of “unsung hero” and be championed as one of the twentieth century’s most valuable role models.

Our two films screening this Sunday are not enough to do that, but they are a start.

The release title of the film, taken from an off-color line delivered by Dick Gregory, was IT WON’T RUB OFF, BABY.