BEFORE I turn over this post to my erudite co-conspirator Phoebe Green, here’s a quick update about THE OTHER SIDE ‘23 as we approach our second weekend. A very few single seats remain for this weekend’s eight-film denouement; do please consider joining us. We move into the 1940s and conclude on Sunday evening with a Micheline Presle tribute that has inspired an exceptionally kind tout from Mick LaSalle (which you can read here). Ms. Presle, still with us at age 100, is definitely deserving of any & all accolades: you may be seeing more of her in our prospective OTHER SIDE ‘24 series.

And now please enjoy Phoebe’s take on our Saturday evening double bill, also eminently worthy of your attention. We hope to see you this weekend!

IT’s possible to see the Occupation Era as bracketed by two films of youth, Premier rendez-vous (1941) and Les petites du quai aux Fleurs (1944)—both apparently featherweight, but with hidden depths and notable divergences.

DD: Danielle Darrieux

Premier rendez-vous, one of the first new French films released after the Nazi occupation was established, delighted everyone. Audiences stood in line for hours to reconnect with their sweetheart, Danielle Darrieux (known in French movie magazines as “DD”), in yet another romp directed by her avuncular older husband, Henri Decoin (Abus de confiance, Retour à l’aube and Battement de Coeur). Continental Films, its German-owned producer, had its first hit.

The collaborationist press, as cited in Christine Leteux’s magisterial book, Continental Films: French Cinema under German Control, welcomed “a healthier idea of filmmaking,” free of “propaganda by agents of social disintegration whose origin is not difficult to guess.” True, Decoin had signed with Continental grimly and reluctantly; true, Darrieux’s marriage was breaking up in favor of a liaison with Dominican playboy Porfirio Rubirosa[1]; true, the screenplay was, in fact, written by the Jewish Max Kolpé, in hiding and shielded by Decoin…

The scenario: Darrieux charms her fellow orphanage inmates into covering for her while she conducts a courtship by letter through a Lonelyhearts ad. (Throughout the film she exerts the sweetly conquering bossiness of Shirley Temple.) When she finally meets her correspondent, he is a middle-aged man (Fernand Ledoux, aptly named) who is horrified to realize she is only a girl—a disappointed one at that—and tells her he is merely standing in for the real correspondent, who is handsome and young. A missed bus and fear of reform school send Darrieux home with Ledoux, who shelters her chastely on the grounds of the boys’ school where he teaches. The unruly schoolboys include Georges Marchal and Daniel Gélin—among their earliest screen appearances.

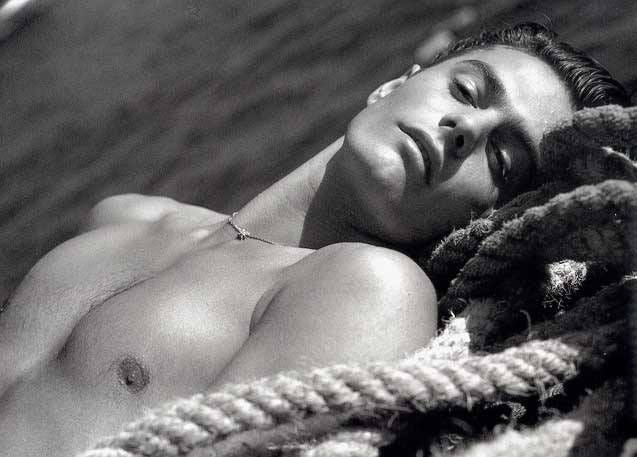

The teacher’s nephew arrives unexpectedly in the ravishing form of Louis Jourdan, a naval officer candidate. Through various screwball developments, Darrieux assumes he is her mystery man; he is duly enamored of her; the obstreperous students spearhead a move to have the teacher adopt her out of the orphanage and the peril of reform school; and she and Jourdan ride off into the future.

One of the film’s striking elements is a somewhat callous valorization of youth over age. “I’m quite harmless,” Ledoux says, humbly. “Men my age don’t place newspaper ads, nor have they the physique to attract pretty young girls like you.” “That’s true!” Darrieux agrees, smiling sweetly. Ledoux is unable to control his mocking students until Darrieux scolds them (she also scolds the principal, for good measure).

Those students are given an interesting showcase: when Darrieux awakens after her first night in Ledoux’ house (a disturbingly noirish sequence: our heroine must barricade her bedroom door), it is to sunlight through the window and a Riefenstahlian low-angle view of the boys’ joyous games and exercises. The last line of the film, after Jourdan has chased after and leaped onto Darrieux’ departing train, is Ledoux’s “I’d never have caught it. Youth, that’s the only thing.”

There is a trace of decadence in this film—we sense a trick that’s become a bit too familiar. Darrieux has played the adorable ingénue too many times: her stardom burns through her role. The mise-en-scene sets her apart in the midst of any crowd, centered and flatteringly lit in the orphanage, surrounded by the students like a leading lady among chorus boys, waving from the door of a train as though acknowledging autograph seekers. The only difference is that she finds her happy end with, not the usual father figure, but a young man.

DD: Danièle Delorme

Marc Allégret’s Les petites du quai aux Fleurs is another story of youth, again revolving around a wide-eyed ingenue (Odette Joyeux, 30 years old and a mother, yet eternally apt in her portrayal of adolescent angst). But let’s focus on the film’s youngest actress: Danièle Delorme (née Girard), appearing for the first time under that name.

This name change was not merely to acquire the lucky double consonant favored by many performers. The Girard family was part of the Carte resistance network—the father in London with de Gaulle, the mother arrested by the Gestapo. (In Delorme’s memoirs, she describes escaping her own arrest and rejoining Allégret: “You must absolutely come back to La Victorine—there are two more days of shooting to do,” he told her. When she was able to take shelter with some courageous friends of the family, she was still wearing her costume’s red shoes. Her mother, meanwhile, imprisoned in Marseille, glimpsed a local paper with a production still from Les petites featuring Danièle misidentified as another actress. The Gestapo had told Mme. Girard that they had captured her daughter, but now she was reassured: “If that isn’t just like Danièle!”)

THE scenario: Joyeux is 16-year-old Rosine, the next-to-youngest of the four motherless daughters of a lovably eccentric bookseller (André Lefaur). She, in secret, is tempestuously in love with her oldest sister’s fiancé (Louis Jourdan), to the point of threatening him with her suicide. The fiancé and a mild-mannered doctor accidentally drawn into the drama (Bernard Blier, adorable) exert themselves to return Rosine to her family without alarming them, but love and lies weave a web that ensnares everyone until things reach a bittersweet resolution.

We note the recurrence of actors and types: Jourdan is again the jeune premier—his first film roles were for Marc Allégret (Le corsair, interrupted by the declaration of war in 1939, and La comédie du bonheur). Daniel Gélin makes a brief appearance in a party scene. Blier’s tender and self-sacrificing role is much like Ledoux’s in Premier rendez-vous.

And here are fresh new faces: Danièle Girard aka Delorme. Also cast was her former lover, now friend, the ethereal Gérard Philipe. (Allégret had wanted them, at the ages of 19 and 15, for the adolescent couple in Colette’s Le blé en herbe. Alas, neither was “name” enough to attract financing; the book remained unadapted until Claude Autant-Lara’s 1954 version.)

The film was shot in the South of France, in Nice, at the Studios de La Victorine, a hotbed of cinematic activity during the Occupation (many actors and technicians fled south to the unoccupied Riviera). The cast of Les petites lived and ate together, sometimes with rooms at the Negresco, sometimes pooling potatoes, in a magically carefree bubble.

THERE is a freshness and an unexpectedness to this film—the dénouement will surprise you—that is in complete contrast to the established Decoin-Darrieux genre. Instead of the clear star-ensemble hierarchy of Rendez-vous, Les Petites is a narrative democracy featuring a well-characterized quartet of sisters. Their shared bedroom, shabby but light-filled and lovable, is exquisitely captured by master cinematographer Henri Alekan. (He also creates a gauzy, sinister dreamworld with dimmed lights during a party game.)

The film turns toward home and family as Rendez-vous (going from orphanage to boarding school to a train towards a new life) did not. There is even a paterfamilias who, though eccentric, cuckolded and abandoned by his wife (and called by his first name by his daughters), can issue a decree of banishment to an erring child and still be obeyed. The film’s last moments reminded me of both Giulietta Masina’s walk among the singing young people in Le Nozze di Cabiria and the creampuff in the childhood scenes of Once Upon a Time in America. Youth will have its way, venerated especially during a wartime that’s been kept at arm’s length throughout the film.

The Liberation was a little over a year away when Les petites finished shooting. Danièle, returned to Paris, would soon be able to welcome her mother back from a Czechoslovakian concentration camp. She and Gélin would marry and form the emblematic St. Germain des Prés couple, “The Daniels.” In 1949, she would become a star in Jacqueline Audry’s Gigi; a few months later, he would embody post-war youth in Jacques Becker’s Rendez-vous de juillet.

[1] This affair lay behind Darrieux’s participation in the notorious trip to Berlin with other Continental stars; she was able to trade her appearance there for Rubirosa’s freedom from German internment and return to France with him. (These events would have a significant effect on her personal life and her future career.)