NOIR ON THE SEA & IN THE FOREST...

March 13 at the Roxie: Astonishing lost works from 50s Germany

The “international noir” side of Midcentury Productions isn’t as well known as our efforts with the “lost continent” of French film noir, but it is also a rich area of discovery that we’ll be revisiting as part of MIDCENTURY MADNESS.

Click the links above and you’ll see the program descriptions for those shows, held in 2015 and 2017—films literally from around the world; oddly, however, among the more than two dozen films screened, there were none from Germany.

“Rubble films,” made immediately after WWII, are known to many for their dark themes and stark visuals featuring bombed-out ruins; but the historical consensus is that once the 1950s arrived, German filmmaking steered itself into complacency, with the heimat film attempting to sidestep (if not outright bury) lingering issues from the Nazi era.

Such began to change when expatriate directors such as Robert Siodmak returned to Germany after the war; Eddie Muller referenced this in his 2020 festival with a screening of THE DEVIL STRIKES AT NIGHT (1957), one of the first German films to directly address the Nazi era.

BUT what we’ve discovered—thanks in part to our colleague Marc Svetov—is that the “noir impulse” still had a pulse in German filmmaking prior to Siodmak’s return. Directors such as Helmut Käutner and Peter Pewas, who had sidestepped/wrangled with the Nazi censors during the war, found their voices afterwards and moved from “rubble films” in the late 40s to film noir in the fifties.

And, as you’ll see on March 13, both of them did so with a vengeance.

Käutner’s EPILOG (1950) is a fever-dream wrapped inside a series of mysteries centered around the sinking of the Orplid, a luxury yacht rented by an arms dealer under strange circumstances—the wedding of his mistress! And, as we soon discover, it turns out that there are much darker forces afoot…

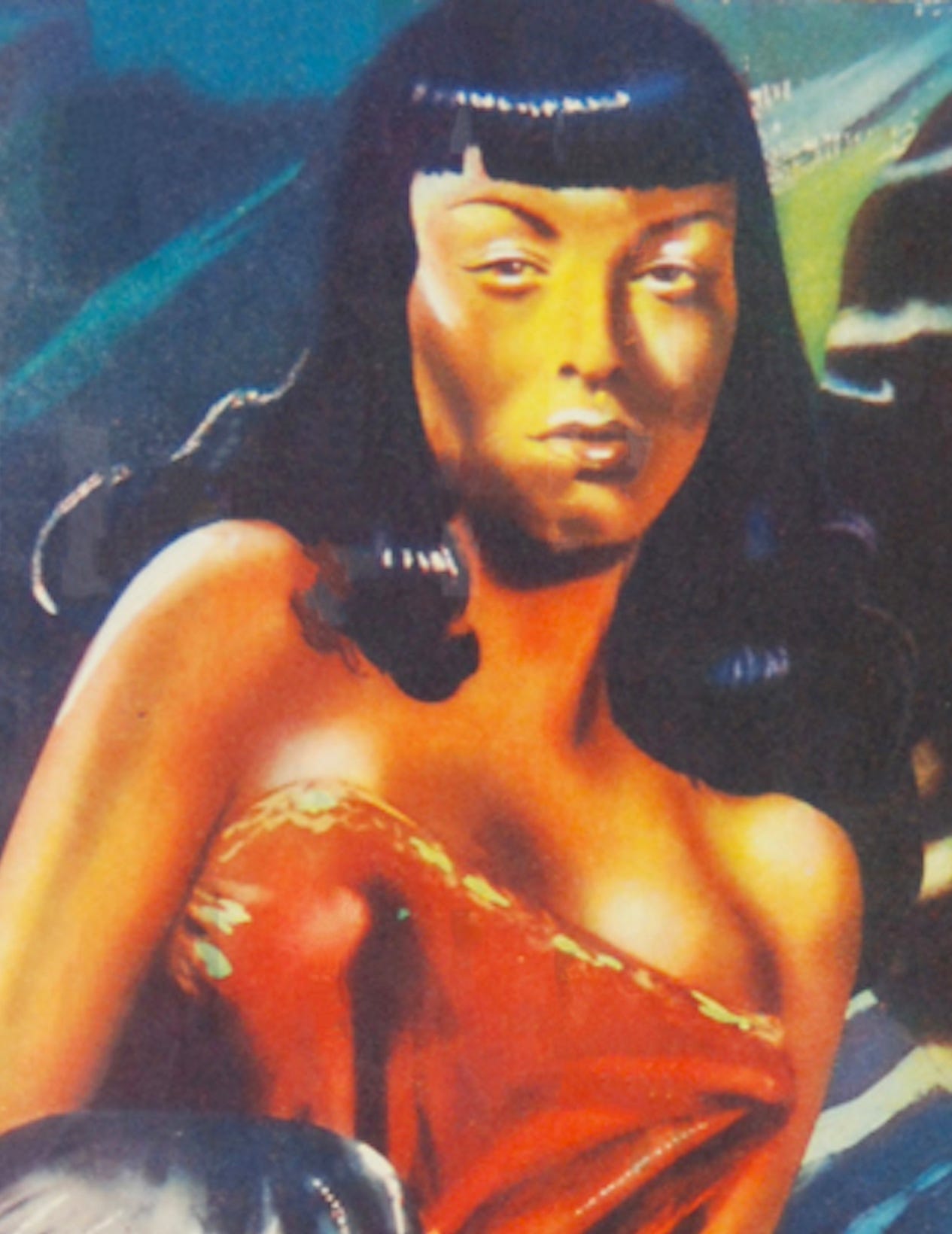

Intrigued by the coverup of this event, reporter Peter Zabel (Horst Caspar) begins an obsessive quest to reconstruct what happened—aided by the mysterious, Sphinx-like—indeed, mute—lone survivor of the catastrophe, Leata (Bettina Moissi), whose drawings provide clues to the sordid goings-on.

Naturally there are clandestine forces that want to prevent Zabel from bringing the full story to light, and EPILOG careens between these narrative shards in a way that is both thrilling and baffling, using all of the favored devices of film noir.

Film scholars and bloggers have known about EPILOG for quite awhile, yet the film has never been screened theatrically in the USA in the seventy-two years since its release. Its long-overdue premiere on March 13 will introduce you to one of the most fascinating female characters in all of noir in Moissi’s Leata, who is even more enigmatic than the mystery of the Orplid itself. Käutner provides us with a sly preview of an emerging “female gaze” in the sloe-eyed, traumatized Leata, who embodies an inchoate “Other” attempting to penetrate and disrupt a world that barely bothers to conceal its ugly and unspeakable truths.

As was the case some years ago when I first saw Christian-Jaque’s VOYAGE SANS ESPOIR (1943), I was overwhelmed by the concentration of “noir energy” achieved in EPILOG. The film has many reverberations—aesthetically, culturally, and politically—and it will leave you with much to contemplate.

AND a different form of that “noir energy” can be found in MANY PASSED BY (1956), which transfers the action from the sea to the nocturnal forests adjacent to Germany’s autobahn—where a serial killer lurks, preying on young girls.

As Marc Svetov relates, director Peter Pewas—possibly the most talented filmmaker in Germany during the 40s and 50s—was a thorn in his own side; he antagonized Nazi censors with his first film THE ENCHANTED DAY (1943), brazenly returning to themes and characters from the “decadent” Weimar school. He also had difficulties in East Germany when he was “one and out” with DEFA in the aftermath of creating the “rubble” drama STREET ACQUAINTANCES (1948). Marc sums up Pewas’ problem succinctly (and diplomatically):

He was far too unconventional as a director and artist to conform very well with the East German Communist regime.

And that unconventionality led him to conceive of MANY PASSED BY as a version of RASHOMON, with competing (and, in some cases, overlapping) narrative sections reflecting three points of view: the serial killer, his intended victim, and the harried investigator attempting to prevent another murder.

Even in our post-MEMENTO age, this was a risky narrative proposition, but Pewas carries it off with only a few hiccups along the way, with suspense maintained to the end. He is also aided considerably by the exceptionally atmospheric photography of Klaus von Rautenfeld, who not only handles the customary noir lighting that one would expect in a mostly nocturnal tale, but also creates uniquely evocative twilight moments in the natural settings. I suspect that his work will evoke similar responses to what Marc Svetov was moved to describe in his examination of the film:

…his means for poetically realizing what he wished in the film are minimalist, yet so effective: the night scenes along the highway, the slick highway surface, the fog in the early morning; the starkly outlined silhouette of the woods, the place of the murders against the night sky; the interior scenes in the café along the highway, the dimly lit police station; the scenes at the home of the detective who is desperate to capture the killer…one must deem MANY PASSED BY as one-of-a-kind for its era.

While von Rautenfeld worked constantly over the next fifteen years, Pewas never made another feature film after MANY PASSED BY: he was relegated to documentaries and short subjects until his death in 1984. It was a daunting fate for a man who made such a haunting film. But he left behind a highly accomplished noir that handles what is now a familiar subject in an intriguing and unusual way.