[For those who’ve asked, the all-festival pass price for “Auteures” is $89, and these will go on sale on Monday, March 4. Single seats for the Little Roxie portion of the series will be available starting on Monday, March 18.

We continue our previews with Phoebe Green’s charming look at the action and personages involved with the creation of our two delightful Jacques Becker films, Antoine et Antoinette (1947) and Rue de l’Estrapade (1953), which comprise our matinée offering for Sunday, March 31. As is always the case, Phoebe has a vast storehouse of information to share, so let’s get to it, shall we?]

Jacques Becker and His Female Collaborators

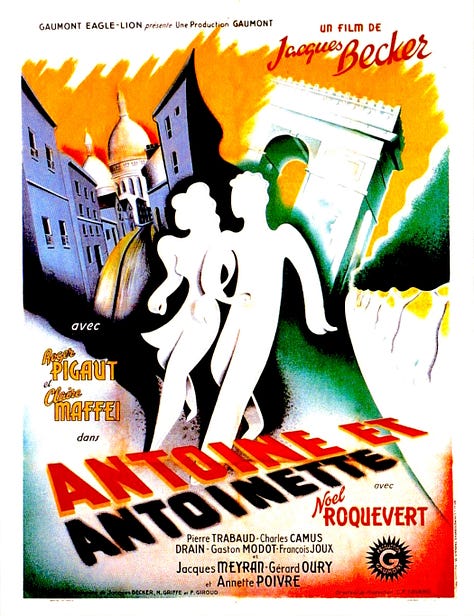

ANTOINE ET ANTOINETTE: A FRENCH TWIST ON A “RUSSIAN” STORY

In 1946, Jacques Becker wanted to make a film about the sort of “little people” treated in David Lean’s This Happy Breed. Together with a couple of writers, including Françoise Giroud, who had been script girl on Jean Renoir’s La grande illusion when Becker was assistant director, he began roughing out a script from an idea by Louise de Vilmorin:

“There is a working-class couple with a little girl, they love each other very much; they’re all very sweet and sympathetic. One day the wife wins the lottery. The husband loses the ticket and, after this enormous blunder, doesn’t dare return home. He disappears completely and the wife remakes her life with another man. A few years later the husband returns and the little girl brings them together again.”

Becker reminisced: “One day I realized the husband simply couldn’t behave in that terribly ‘Russian’ way… A French audience would find the psychology fundamentally unbelievable… So I left that part out and had him come back, ashamed, and so forth.”

In the original story idea, the man with whom the wife remakes her life is a black-market restaurateur. Becker transformed this character into a lecherous grocer (a hissable turn by Noël Roquevert), who, in the postwar Paris of shortages and ration tickets, can still exploit considerable power over his clientele. Vulnerability seems to shadow all the protagonists’ triumphs and joys: even the winning lottery ticket is issued by the Gueules Cassées, the association of facially disfigured WWI soldiers. Our first view of Antoine (Roger Pigaut) in the bookbindery shows his skillful hands frighteningly near guillotine-like machinery; a minor character’s rendezvous with a two-timing wife, the stuff of smutty jokes, nonetheless involves death-defying clambering from window to window.

In this atmosphere, Antoinette (Claire Maffei) shines with joy and hope. Becker, as Françoise Giroud wrote, “was one of those men who think that women play a great part in life, though [these men] may not be able to define it exactly, a part that may not always be amenable to reason, but is very powerful, and that therefore one can’t speak of life without speaking of women.”

BECKER AND WADEMANT: TWO WITH ANNE VERNON

A year after the release of Antoine et Antoinette, at the auditions for his postwar youthquake of a film, Rendez-vous de juillet, Becker met a young Belgian actress going to film school in Paris, Annette Wademant. She was not cast, but the two moved in together and collaborated on an extraordinary couple of films, Edouard et Caroline and Rue de l’Estrapade, starring and, in the latter case inspired by, the actress Anne Vernon.

Vernon, in her memoir Hier, à la même heure (Same Time Yesterday), remembers how it all began: “An old acquaintance, Jacques Becker, wanted to meet me for [Edouard et Caroline]. We agreed to meet where he was living, at his friend Clouzot's place near Notre Dame. A superb creature opened the door for me: tall, fresh, dazzlingly blonde. No doubt she had just been cast in the part. No, extraordinary thing: she was the writer of the film, Annette Wademant! I couldn't take my eyes off her lovely laughing face. But yes, it was she whom I had noticed in Brussels among the heavily made-up adolescents competing for the title of Miss Ciné-Revue a few years ago. There she had stood, in ankle socks and flat shoes, head lowered, with a little sidelong smile. Annette Wademant began to laugh: she remembered me too! After being elected the periodical’s beauty queen, she had been Miss Brussels, then Miss Belgium, which had taken her, like me, to Hollywood.”

Anne Vernon, née Edith Vignaud, fascinated by the visual arts, matriculated at the Ecole Duperré, a school of applied arts for girls, and as a teenager was hired by Marcel Rochas as a sketch artist and designer for his couture house. (Echoes of Becker’s Falbalas!) Monsieuer Rochas—“slightly exotic, romantic, unctuous, pomaded...he even, I was told, liked women!”—will reappear in the person of Jean Servais as couturier Jacques Christian (likely a nod to director Christian-Jaque) in Rue de l’Estrapade.

When the Maison Rochas added a dedicated cinema costume department, Vernon studied the actors who came for fittings and was scouted for a screen test. Viewing the footage, she was astonished by her own photogenicity. “You’ve got something, you’ll be in movies,” remarked a neighbor at the screening: Simone Signoret. And so she was, eventually appearing in forty of them. But her true love remained the visual arts—and today, having celebrated her 100th birthday this past January, she lives and paints in her beloved Cogolin on the Gulf of Saint-Tropez.

Vernon remembers the filming of Edouard et Caroline as stressful: “Becker and Annette Wademant, one as creative as the other, but differently, argued constantly… But when a woman has been able to remain feminine, her contribution to a film is capital. She knows how to make meaning out of what men consider trivial. So, while Jacques’s back was turned, Annette would move the camera. He then showered her with insults, and they went so far as to exchange blows, which they seemed to forget afterwards immediately.”

Edouard et Caroline, despite a stingy budget and rushed schedule—the producer having no confidence in a script written by “that beauty queen”—was a hit at home and abroad, competing at Cannes, then English-dubbed and playing in the US. François Truffaut picked out a salient detail: “That scene…where Elina Labourdette makes ‘doe’s eyes’: to recognize it as filmable, it was necessary first to have witnessed it in real life, then thought it through ‘as a director.’ I don’t know if we owe that scene to Annette Wademant or Jacques Becker, but I’m certain that any other director would have taken it out of the storyboard. It doesn’t move the action one step forward; but it is there above all, it seems, to give a touch, not of realism, but of reality…”

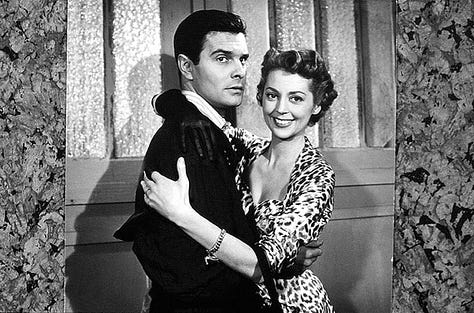

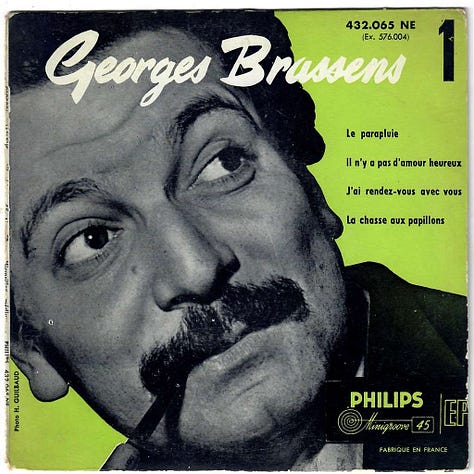

Rue de l’Estrapade presents a young wife (Vernon) who discovers that her husband (Louis Jourdan) is stepping out on her. She responds by leaving the conjugal domicile, taking a garret room on the Left Bank, and attempting to get a job in a couture house. She is pursued by a moody young scrounger down the hall (Daniel Gélin), but, though amused and tempted, returns home when her husband comes to woo her back. Not much of a story? Perhaps, but the film enchants us by the details and characters that spring out from this slight framework: the monologues of the couple’s maid; Gélin’s speculative stare at Vernon’s fur coat; Georges Brassens’s song Le Parapluie.

Rue de l’Estrapade was avowedly based on an adventure of Annette Wademant’s, in which she left her live-in lover and briefly took up with the young Robert Hossein in bohemian poverty. In a magazine interview, she said that this lover was Belgian, who traveled from Belgium to retrieve her. In a short documentary film on Daniel Gélin’s career, however, Hossein indicates that the lover was Becker himself.

Whatever the case, there is a sense of farewell even as Vernon and Jourdan reunite and drive off together at the end of the film. Gélin, looking down from his garret window, murmurs: “You see, she's going and she'll never come back.”

And, for whatever reason, Rue de l’Estrapade was the last collaboration between Becker and Wademant. (Becker would shift gears with Touchez pas au grisbi; Wademant would next lend her feminine perspective to Madame de…, adapted from Louise de Vilmorin’s novella and one of Max Ophuls’ most celebrated achievements.)

[Remember, all-festival passes for “Auteures: the Other Side of the Lost Continent ‘24” will be available starting on Monday, March 4. Previews of all 15 films, mostly written by Phoebe Green, will appear here as we continue the countdown to March 30. Please join us!]