The more we probe into the details of “Auteures” (aka THE OTHER SIDE OF THE LOST CONTINENT ‘24), the more exciting the series becomes. There’s a fascinating “gear shift” in the series on Sunday evening (March 31) that takes us into a more elemental aspect of women’s lives. As provocative and entertaining the first six films in the series are, LA MATERNELLE and L”AMOUR D’UNE FEMME combine to up the ante in ways that I’m certain will be palpable to the audience.

(Phoebe Green has once again done her homework, and she will now guide us into the very real world of LA MATERNELLE; I will try to keep up with her work on Monday when I preview L’AMOUR D’UNE FEMME, with the intensely luminous Micheline Presle…)

La Maternelle

Marie Epstein did not work alone. She collaborated first with her brother, Jean Epstein, cinematic theorist and innovator, then the documentarist Jean Benoît-Lévy, and was recruited by Henri Langlois as film preservationist at the Cinémathèque Française, saving the work of others (including her brother) from oblivion. Not precisely an auteur as the term was conceived, not the single signatory of the work, but indelible nonetheless, a matrix of inspiration and influence. La Maternelle (1933), the work for which she is best known, reflects or prefigures this praxis: nothing is achieved without hands-on cooperation.

In La Maternelle, Rose (Madeleine Renaud, with a face half-madonna, half-doll) is an heiress about to marry, but the loss of family and fortune sends her alone into the working world. She takes the first job available, a maid-of-all-work in the titular child care center. We see this set-up through silent-film signifying: the ring on the finger, the finger bare on a hand clutching a black glove.

From this stagy beginning, we pass into a documentary-style world of real locations and non-professional child actors. We also pass into a female environment, presided over by a rule-bound principal and an earthy head maid, startlingly introduced first singing a syrupy romantic ballad, then throwing a mouse into the kitchen fire.

Rose immediately enchants Marie Coeuret, an intense, love-hungry little girl played by the phenomenal Paulette Elambert. Marie’s own mother is a tart who abandons her for a sleazy lover; Rose takes the child in.

Until nearly the end of the film, men are a threatening and disruptive occasional presence. Doctor Libois, the school supervisor, is introduced as a voice on the phone indignant that Rose has been hired instead of his protégée. The father of some of la maternelle’s children is a drunken brute who demands to kiss Rose in exchange for not beating his offspring. (An unsubtitled exchange between two little boys, one with a black eye: “Did your father do that?” “Yes.” “Your mother must have a rough time!”) An ambiguous exception is a visiting professor of psychology, whose experiment on the class involves a rabbit: food or pet? He is delighted when the class turns against him to defend the rabbit, a mob of tinies shouting “salaud!” at him.)

The film incorporates stylistic elements from both Epstein’s cinematic collaborations: not only the documentary approach, common to her brother and to Benoît-Lévy, but a plunge into the little girl’s subjectivity through lightning-fast montage and juxtaposition, repeated images charged with successive overlays of meaning. How many different roles does a ship, as toy or drawing, play here?

Although there is the requisite happy-ending-through-marriage, its importance is supplanted by two extraordinary moments: the hulking head maid’s tribute to Rose’s care of the children, and a demonstration by her fiancé, Dr. Libois, that he has absorbed Rose’s lessons. The last shot of the film is not a wedding, but children walking through a light-flooded gateway into whatever lies ahead. Not a single, emblematic child, facing the future alone—but two of them, holding hands.

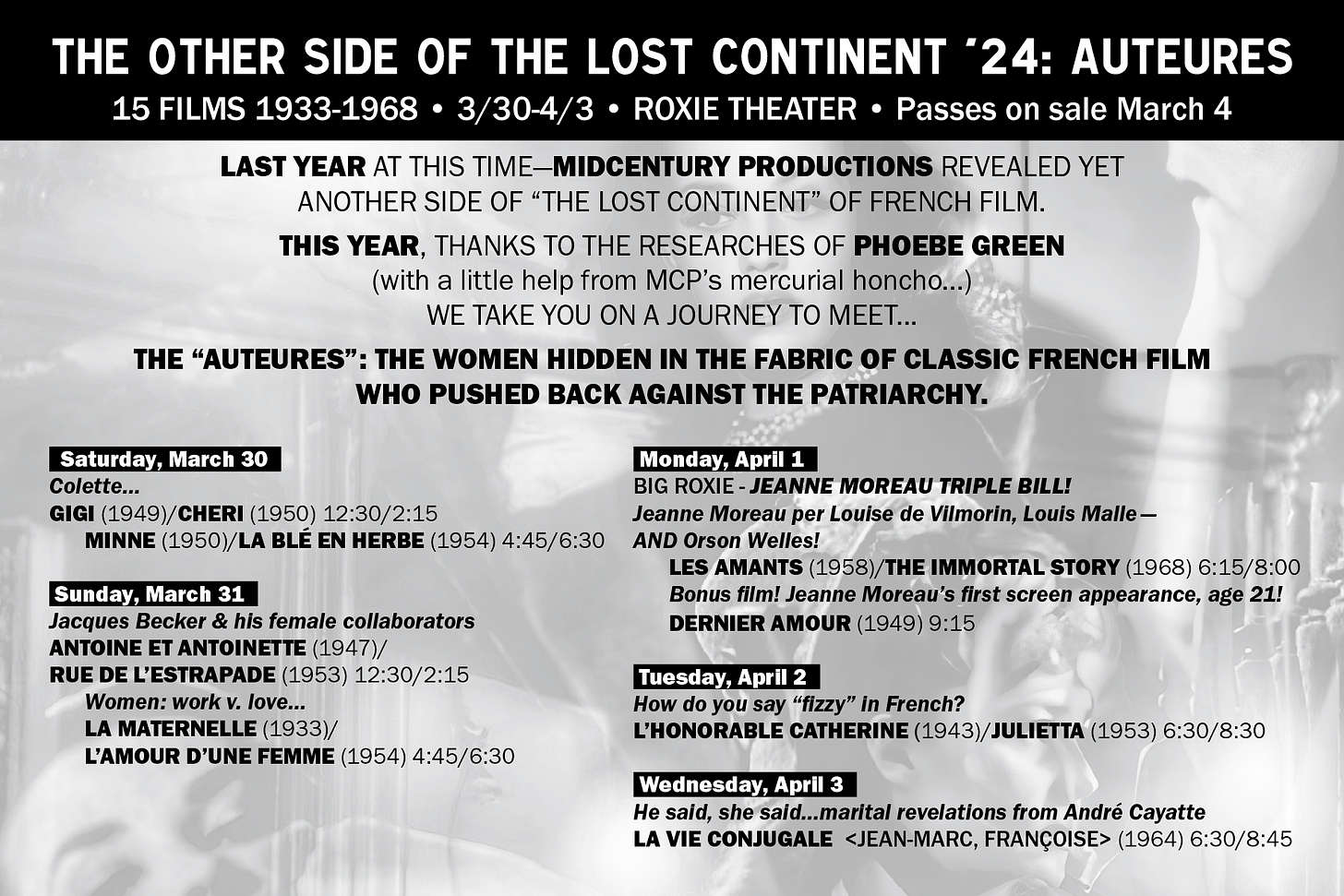

[All-festival passes—all 15 films for $89—remain on sale via this PayPal link. Once again, here is the full schedule for THE OTHER SIDE ‘24…we look forward to seeing you at the Roxie!]