A frustrating travel update: the storm currently in the Bay Area is heading south tonight, bringing intense rainfall here in Santa Barbara overnight—and due to the particular household vulnerabilities here that many in the “film club” have heard about between films over the past year, I will be delayed in arriving at “Auteures” until mid-afternoon Sunday.

Fortunately, you will be in good hands until my arrival with Phoebe Green, who will introduce the films in my stead. Please give her a big hand—for, as you know, she is the true prime mover of “Auteures” and will guide you well. I look forward to seeing all of you on Sunday!

IT has been sixty years since “the lawyer of French cinema”, André Cayatte, released one of his most ambitious experiments, one totally in keeping with the social interests that had been consistently derided by the critics at Cahiers du Cinema. (That “lawyer of…” label was not one meant in praise!)

I’m hoping to showcase more of Cayatte’s work this fall (as part of a scenario for a more expansive conclusion to FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT), for he is someone we’ve only seen occasionally in our series thus far. Cayatte had an affinity for what I call the true French style of noir, the version not associated with the “big American car/existentialist gangster” series that came to dominate in the 1950s and usurped the noir-melodrama synthesis that had emerged just after World War II. One of the finest noirs in that 1946-53 time frame was the elegant-yet-fraught LES AMANTS DE VERONE (1949), a superb collaboration between Cayatte and Jacques Prévert—one of the great hits in our 20-film lineup for FRENCH 5 in 2018.

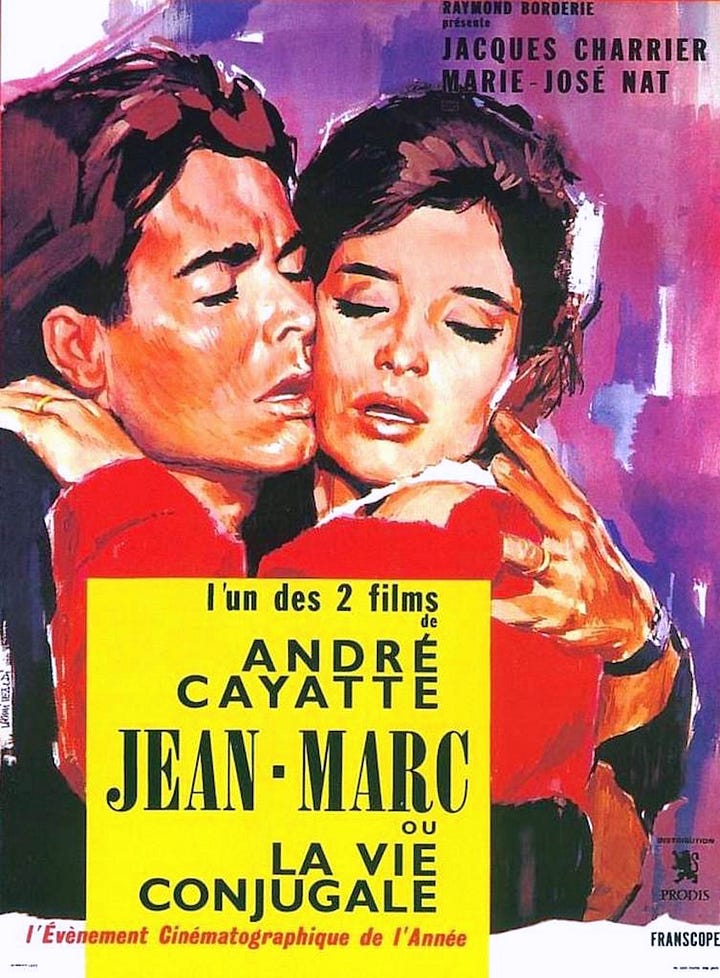

From that point on, Cayatte mixed noir with social issues, and his output into the late 1960s fully deserves its own “auteurist” retrospective. The two films that comprise our closing night (April 3), LA VIE CONJUGALE: JEAN-MARC et FRANÇOISE (1964), are clearly melodramas, but as with much of Cayatte’s work, they crash the barriers between film and real life to depict the state of gender relations and marriage in a unique way.

Many modern film narratives dealing with “the battle of the sexes” tend to interweave the male/female perspectives—an artificial construct that has become accepted as a necessary shortcut to ensure audience engagement in the age of ADHD. Cayatte’s original idea would have followed this approach, but as he began mapping out the early stages of the film with Simone de Beauvoir, it became clear that such an approach was producing something unwieldy and ultimately unbalanced. (It also seems that de Beauvoir wanted more overt strength to be displayed in the character of the wife, which Cayatte felt would remove too much of the emotional difference between men and women.)

Unable to reconcile those issues and create a single film that could encompass them, Cayatte decided to make two films that showed the arc of a young French couple’s engulfment with one another, showing the events as each perceived them separately. Though he’d parted with de Beauvoir, Cayatte would later indicate that he had tried to incorporate her perspectives by giving the woman’s story the last word.

WHAT comes from this is a fascinatingly nuanced cumulative effect as events related to us in the JEAN-MARC tale—narrated by Jacques Charrier, whom many of you will remember as the jaded young man in Marcel Carné’s LES TRICHEURS (1958)—are revisited with what clearly feels like a corrective effect in the FRANÇOISE tale, narrated by the young Corsican actress Marie-José Nat.

To my mind, it is Nat who grows up from an ingenue to a leading lady as her character revisits and reshapes events in the marital arc, demonstrating the more charged world of woman’s emotions in a world dominated and manipulated by men (a structural situation from which—as usual—Cayatte does not shy away). We see her growth as we see Nat growing from her not-quite-fully-dimensional role as Brigitte Bardot’s rival for the “affections” of Sami Frey in Clouzot’s LA VÉRITÉ a few years earlier into a character engulfed and besieged by her need for agency and finding barriers to it everywhere she turns.

Nat would marry the mostly forgotten filmmaker Michel Drach shortly after making LA VIE CONJUGALE, and she would be his muse for more than a decade, achieving notable success in LES VIOLINS DU BAL (1974), with Nat given the Best Actress award at Cannes. But, like Jean-Marc and Françoise in LA VIE CONJUGALE, they would part from one another—after seven movies and three sons together.

Cayatte would continue with his intense interest in the psychological essence of women in his next film, the fractured-personality noir PIEGE POUR CENDRILLON aka TRAP FOR CINDERELLA (1965), which was featured in FRENCH 6 in 2019. He is a director wholly deserving of rediscovery at a time when the issues he infused into his filmmaking continue to swirl around us. Sixty years later, he is more “relevant” than one might initially think possible.

Needless to say, I’ll be very interested to receive the “film club’s” take on our closing night double feature…