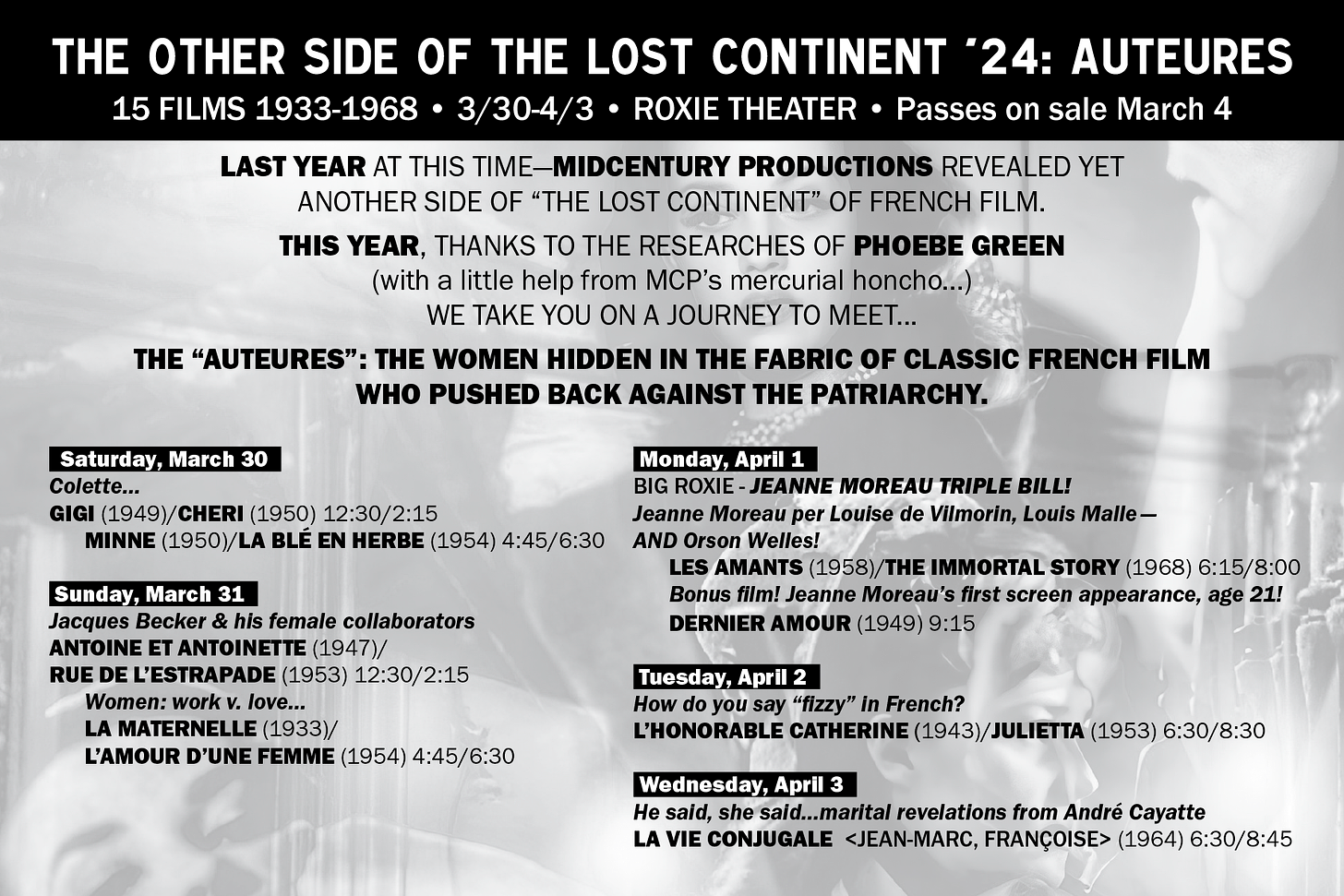

Bonjour to all! “Auteures” clearly had to start with Colette, whose works were finally ready for cinema in the 1950s. Phoebe Green zeroes in on the four films that open our OTHER SIDE OF THE LOST CONTINENT ‘24 series on Saturday, March 30—with hope that her affectionate erudition will start a stampede for all-festival passes when they go on sale (Monday, March 4). The full schedule for the festival is shown on “the other side” of Phoebe’s energizing essay…

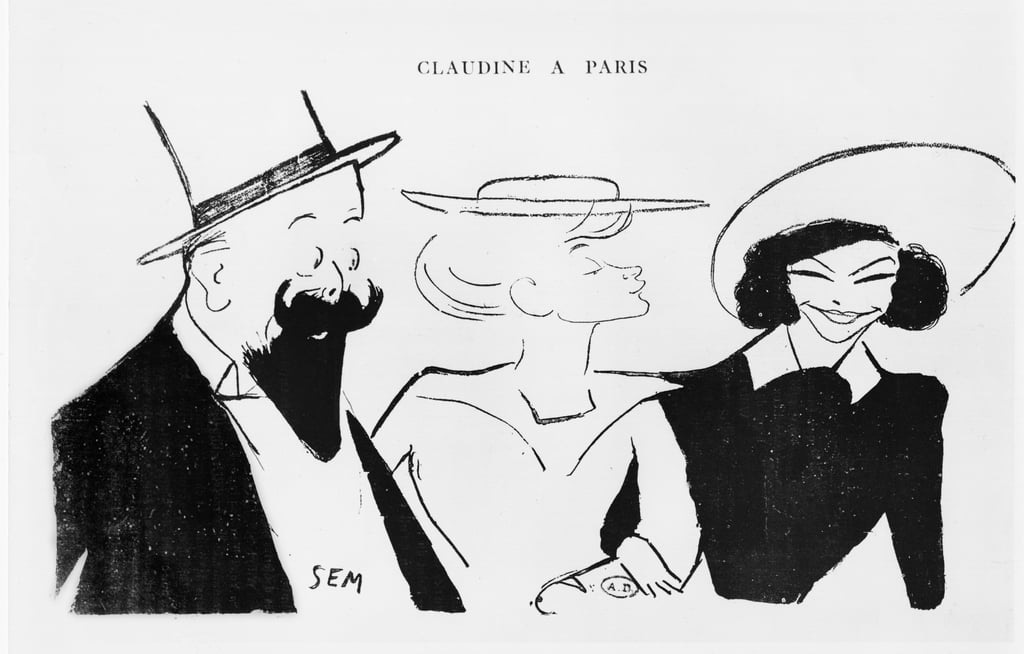

THE grimness of the French Occupation was lightened by one of Colette’s last fictions, Gigi. This was a look back through rose-colored glasses at the Belle Epoque; an era in which, before she was its chronicler, Colette, her then-husband Willy, and their highly visible tertium quid, the dancer Polaire, were prominent media figures.

Colette’s fiction had often veered through her own life, and the social circles in which she (and her various partners) often peregrinated, and Gigi was cut from the same cloth, but with a gauzy, affectionate glow that lingered insistently in the minds of its readers. And it would prove to have surprising repercussions...

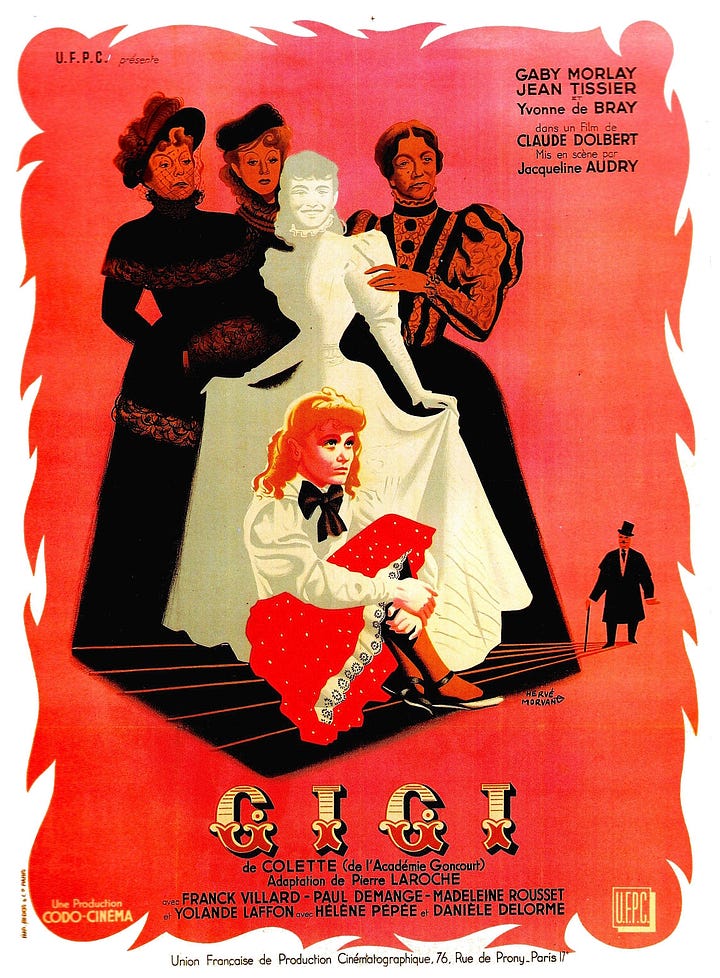

FROM this late, retrospective work there sprang a new director (Jacqueline Audry), a new star (Danièle Delorme), and one might even say a new genre. After the success of Gigi, the cinemas of the French Fourth Republic rustled with Belle Epoque froufrou: not only the three films uniting Audry, Colette, and Delorme, but Ophuls’ La Ronde, Le Plaisir, and Madame de…; Audry’s own Olivia; Becker’s Casque d’Or; Renoir’s Elena et les Hommes; Duvivier’s Pot-Bouille…

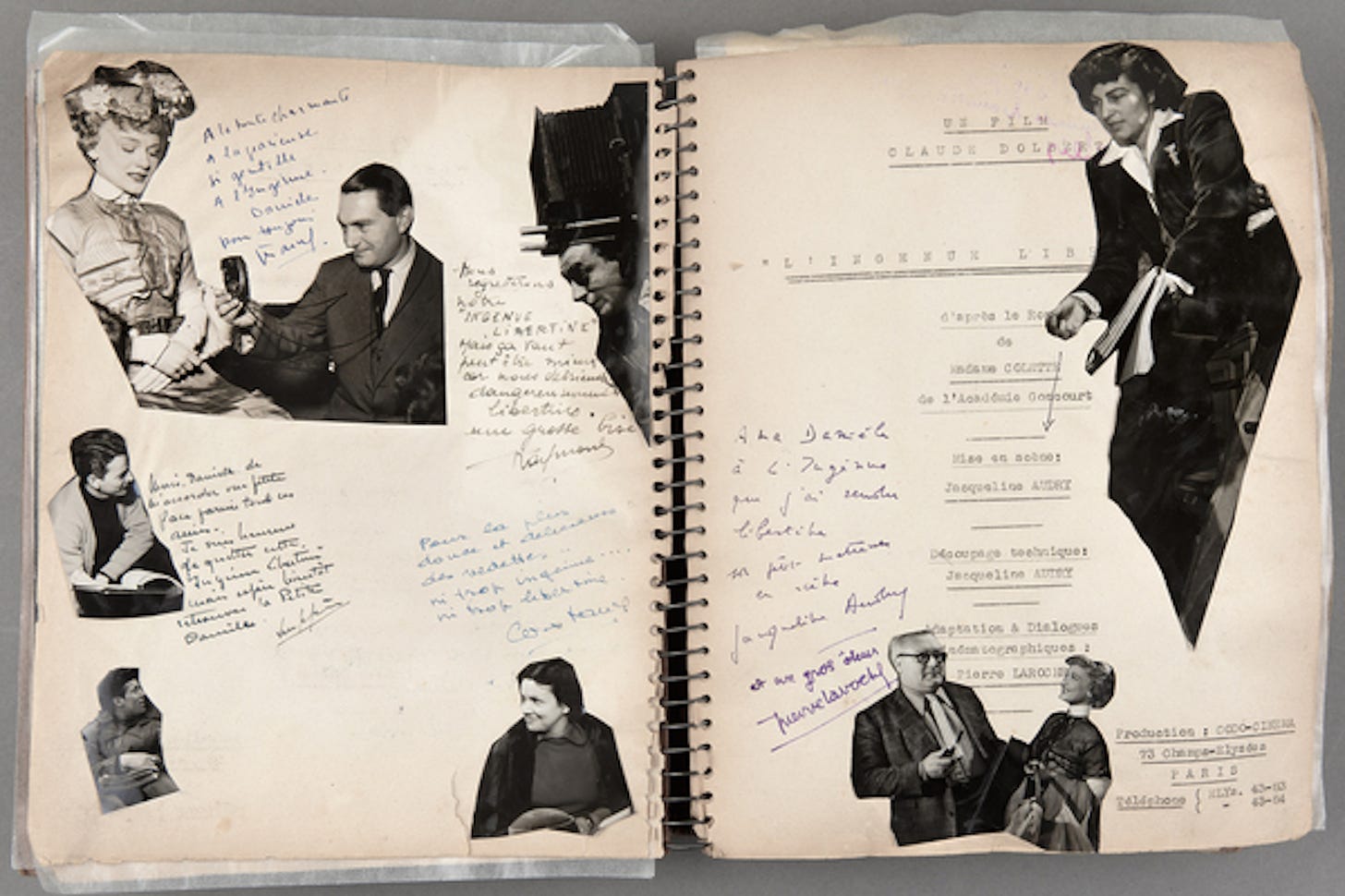

Gigi was a brave throw of the dice for Colette, entrusting a valuable property to a young woman with only one documentary and one feature to her name (although she had been assistant director to Ophuls, Pabst, and Delannoy). The production budget was so exiguous that many interior scenes were shot, Cox and Box style, on the sets of Le Secret de Mayerling, which was filming at the same time. Audry’s partner and future husband, Pierre Laroche, adapted the novella for the screen, adding the character of Gaston’s old roué uncle (the always-welcome Jean Tissier), a past acquaintance of Mamita (the equally delightful and omnipresent Yvonne de Bray). So well-constructed was his script that Minnelli’s lavish MGM musical followed it scene for scene, even using some of the same Paris locations (below, 29 avenue Rapp).

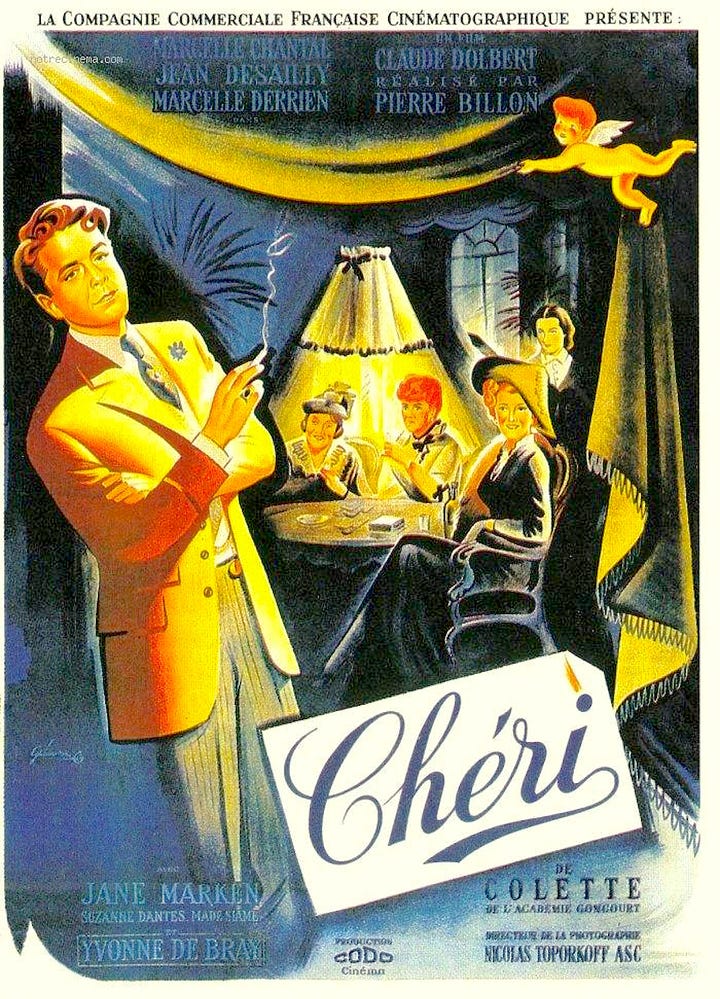

AFTER Gigi, the story of a courtesan in training, we turn to that of a courtesan at the end of her career. Working not with Audry but with the unjustly obscure Pierre Billon, scenarist Laroche masterfully spliced Colette’s Chéri and La fin de Chéri into a shapely script, starring Jean Desailly (who, for this opportunity, ceded the role of the Young Man in Ophuls’ La Ronde to Daniel Gélin) and, in her final film role, the magnificent Marcelle Chantal. (His adapter’s skill is all the more striking when one realizes that the two novels, while chronologically sequential, are in fact thematically opposed.)

Colette, as noted, seems Janus-faced between modernity and nostalgia: she leaps forward in order to look back. One thinks of her marriage and the ensuing ghostwriter’s mind-meld that produced the Claudine novels, which assume the viewpoint of her husband/impresario Willy—who himself adopted the lofty yet wistful salaciousness of a roué twice his age.

Her Chéri and La Fin de Chéri, although apparently and chronologically sequential, are in fact two different perspectives on the same doomed couple: Léa de Lonval, a Parisian grande horizontale nearing the mellow end of a long and remunerative career, and Fred Peloux, “Chéri,” the son of Charlotte, Léa’s friend and fellow courtesan: a beautiful boy half her age. (Jean Desailly, not quite a Valentinoesque heartthrob, still indelibly captures Chéri’s nervy, hopeless boyishness, the petulant misery of a sleepy child who will not go to bed without a promised kiss.)

Pierre Laroche—deserving of his own festival highlighting over 50 films ranging from these Colette adaptations all the way to fully-fledged film noir (Quai de grenelle, Audry’s audacious adaptation of Huis clos, Le septième juré)—solves the construction problem that hobbled the recent (and most unfortunate!) Stephen Frears adaptation by presenting the events of Chéri as a flashback within the closing episode of La Fin de Chéri. The film begins with Chéri running into the Old Pal, immediately after the terrible final visit to Léa (only referred to, not shown). The Old Pal brings him back to her place, where a photograph of Charlotte’s circle naturally dissolves back to the moment it was taken…

FROM courtesans we turn to protagonists whose affairs are strictly pour le sport. The second Colette-Aubry-Delorme outing, Minne: l’ingénue libertine, was a more lavish production, with wittily characterized interiors and a plethora of elaborate underthings.

The work on which it was based was a dipytch of two completely divergent novellas. Colette, venturing away from Willy’s template for saucy fiction, wrote Minne, the story of a sheltered young girl living on the boulevard Berthier, a peculiarly liminal Paris neighborhood of the time, all bourgeois townhouses by day and skulking venturers from the nearby fortifs by night. The demure 15-year-old’s dreams, nourished by the yellow press, center upon a glamorous apache. (Well before Becker’s Casque d’or, she dresses herself as his moll: “Casque de Cuivre.“)

But when she dares to venture out one night in search of her hero, she is bewildered and frightened by those she meets—the homeless, tough old tarts, and a lecherous drunk who tries to pick her up. Fainting in her own front hall at dawn, she is plunged into another nightmare—her gentle mother and doctor uncle swoop down to submit her to immediate medical examination; her cousin Antoine, whose crush on her she has tolerated loftily, sobs at her bedside while she protests, “It’s not true! Nothing was true!”

This bitter little gem received a sequel, L’ingénue libertine (The Innocent Libertine) in the true Willy style. Minne, now married to Antoine, goes on an episodic quest for erotic pleasure. Oo-la-la.

Pierre Laroche again compressed two novels into a single storyline, fitting the climax of the first into a flashback, then following Minne’s adventures from a disappointing wedding night to…well, a happy ending. We may regret the small masterpiece that a cinematic adaptation of Minne alone could be, but the existing film is a great deal of skillful fun. Along the way, Polaire makes another appearance…

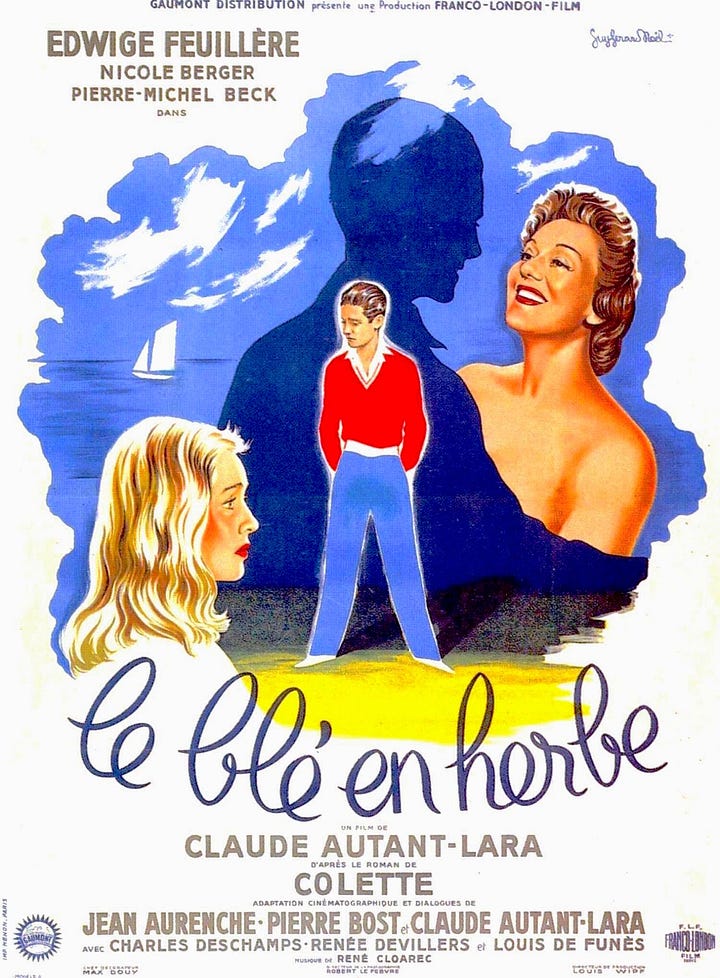

COLETTE’s 1923 novel Le blé en herbe (The Ripening Seed), serialized in Le Matin, so shocked readers that it was cut off mid-sentence. This romantic triangle of two teenage virgins and an older woman is perhaps even more shocking today, not for its allusive sexuality but for its nonchalant acceptance of what is not at all anachronistic for us to call “grooming.” It is worth noting that Colette named its older woman, Mme Dalleray (played by the sublime Edwige Feuillère) after the rue d’Alleray, where the author herself trysted with her 17-year-old stepson. (He emerged from this affair as imperturbable as one of Colette’s adolescent heroines.)

Claude Autant-Lara expanded his 1954 film version with seaside atmosphere and glimpses of cinema circa 1923—and shocked the bien-pensants all over again. As James Travers notes: “It begins with a sequence…conceived expressly to mock the sensibilities of the bourgeoisie: a young man is washed up naked on a beach in front of a party of schoolgirls and prim old ladies, with predictable results.”

And from here, the innuendo turns flagrant (if never en flagrante): Philippe, the young boy, has a very close friend, Venda—a young girl who is as anxiously virginal as he is—and both are struggling with remaining so near (and yet…). Then Philippe encounters Mme. Dalleray, and their mutual interest soon comes to hinge on what we might call “the pedagogy of love.”

The provinces may well have been scandalized, but Autant-Lara had the last laugh, winning the Grand Prix du Cinema Français along with excellent box-office receipts.

The film has languished in the seventy years since its release, however, possibly due to its story having been taken up by coarser minds who made cinema more insistently titillating and explicit. You are urged to see it for Feuillère, of course, but also for the young actors (Pierre-Michel Beck and Nicole Berger) who perfectly embody the bittersweet anxiety of teenaged confusion.

Colette lived long enough to see the film, and she was enraptured by it. Daubing her eyes, she exclaimed: “The magic of cinema has brought my characters before me—in all their anguish and joy.” That magic is still palpable today: come see for yourself!