WE can only do so much in 2022, as the world keeps bobbing and weaving around us: surviving to stand and fight another day (and turning out the vote) will be the focus for many as we move into another fateful fall.

That’s also the position of our embattled French noir festival, THE FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT, which limits its audience size strategically this year in order to maximize our ability to present a series that continues to push forward the notion that the history of French cinema continues to be misunderstood and remains in need of correction. Better that a fraction of our original audience can still fully engage with those notions (and the vibrant, astonishing films we’re still proud to resurrect) than to downsize the scope of our endeavor.

We hope that those of you reading here will move quickly to reserve festival passes for FRENCH ‘22, which will screen 15 films on four days (November 6-7-12-13) in the cozy Little Roxie. Seats are limited, but we think you’ll find that investing your time and dollar in the full reach of this year’s series will be at least as rewarding as has been the case in pre-pandemic times.

There are eleven “new” rediscoveries in the lineup this year, with an increased emphasis on films made during the Occupation period, a tipping point for the uniquely French incarnation of film noir. Mixing/melding of genres is a signature feature of the unique group of films that almost literally “escaped” to the public during the war years, and the “provincial gothic” became a tonality within French noir that retained a special resonance even as it went underground after the Liberation.

The films that present these qualities within our overall FRENCH ‘22 lineup are: GOUPI MAINS ROUGES aka IT HAPPENED AT THE INN (1943), the film that establishes Jacques Becker as a force to be reckoned with in French cinema; LE DIABLE SOUFFLE aka THE DEVIL’s BREATH (1947), a film by Bertrand Tavernier favorite Edmond T. Gréville that absorbs much of the “gothic” flavor of Occupation cinema into its strange, almost mute triangle of characters; LE MAIN DU DIABLE aka HAND OF THE DEVIL (1943), Maurice Tourneur’s symbolic noir-horror hybrid that reminds us of the inexorable resilience of evil, and SORTILEGES aka SPELLS (1945), Christian-Jaque’s snowy tale of a village besieged by a man going mad.

With this quartet of films, we are at last able to see the subterranean dynamic that courses through French noir in the Occupation period, and see how it flourishes away from the standard urban tropes that so often distort our understanding about noir’s ability to create a “nest of vipers” in almost any setting and social structure.

A second group of four films receive repeat screenings, as we honor some of the astonishing discoveries made over the course of nine festivals. The most popular of these is Robert Hossein, whose career as a noir director (1955 through 1970) has been showcased throughout the run of THE FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT. We highlight Hossein the noir actor this year as we reprise what is arguably the best French noir of the 1960s, CHAIR DE POULE aka HIGHWAY PICKUP (1963), directed by the redoubtable Julien Duvivier.

The doomed Hossein’s bitter laughter at the end of this film is a fitting capstone to the noir impulse, and ties together the authentic traditions within noir that span national cinemas. (And it is not by accident that French noir survived and flourished into the 1960s when it was moribund in the USA—one senses that Duvivier, a masterful director of noir since the 1930s—was valorizing Hossein’s efforts in devising what we like to call “the last wave” of French film noir, the fertile period of ferment from 1955-1966 that both recapitulates and regenerates the noir ethos as the mid-century world yields to post-modernist meta-irony.

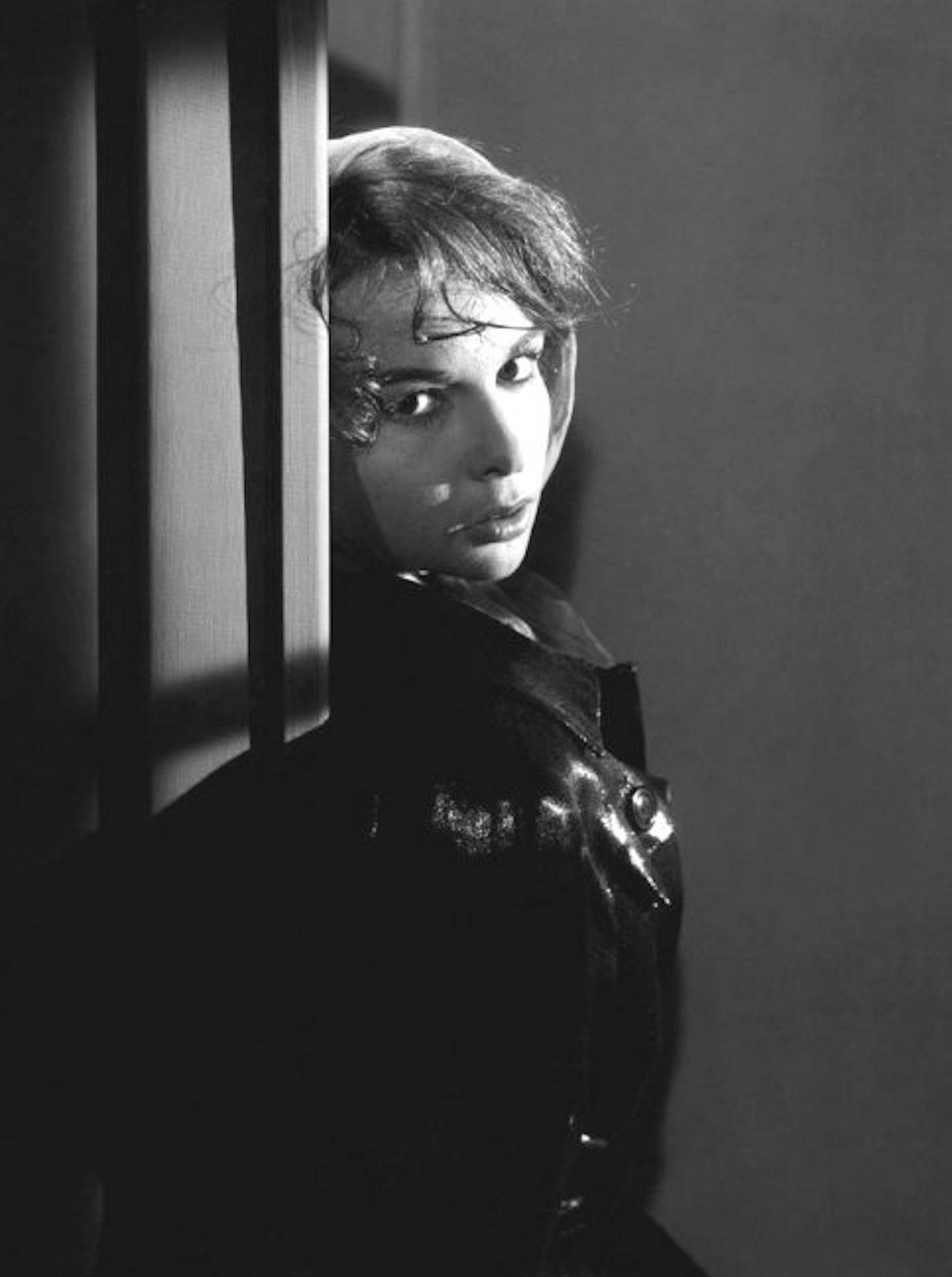

We also reprise two films featuring one of the remaining survivors from that last wave—the criminally overlooked actress Mylene Demongeot, still with us at age 87. Often dismissed as a Brigitte Bardot clone, Demongeot demonstrates superb versatility and serious acting chops in two seminal late-50s noirs, UNE MANCHE ET LA BELLE aka KISS FOR A KILLER (1957, directed by Henri Verneuil) and CETTE NUIT-LA aka THAT NIGHT… (1958, directed by Maurice Cazeneuve). Whether playing a duplicitous, scheming secretary (the former) or a besieged glamour girl with an abusive boss and a harried, hair-trigger husband (the latter), Demongeot is immersed in her character in ways that go far beyond her looks. But she acquired a reputation for being “difficult,” and her career stalled for nearly two decades, leaving these top-shelf noirs lost in the jetsam set adrift by France’s cinematic culture wars.

Our fourth “repeat” reminds us that even the “trash component” of any national film industry can produce unexpected gems, resurrecting and rehabilitating individuals whose careers and images have been sullied by over-exposure and relentless exploitation. Such is the case with LUCKY JO (1964), a film that redeems Eddie Constantine as an actor (and does so without the ironic over-signaling that accompanies his appearance in Godard’s ALPHAVILLE). The film also renews the “crime comedy” subgenre that had sprung up in France at the dawn of the 60s, thanks to the deft writing of Nina Companeez, daughter of the prolific French noir specialist Jacques Companeez.

A honorable but inept loser, Lucky Jo (the name is highly ironic) makes more and more of a muddle as he tries to set things right. It’s a side of Constantine that no one knew existed, and director Michel Deville has blended the elements of crime, romance and comedy in a singular way. Bertrand Tavernier uttered the formerly unthinkable: “In a year when the nouvelle vague was running the gauntlet, LUCKY JO was, in its wry, self-deprecating way, the most satisfying film of that year.”

Three of our films push us to the outer bounds of our time frame, as we showcase the overlooked director Pierre Granier-Deferre. Faces familiar to you in wholly unfamiliar roles have been a mainstay of THE FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT, and it’s no different here: CLOPORTES (1965), still shot in B&W and another film “on the cusp” of “classic noir’s” final implosion, is top-lined by Lino Ventura; THE WIDOW COUDERC (1971), gives us a racier version of a provincial love triangle mixed in with criminous underdoings with a more weathered Simone Signoret and a less-glamorous-than-usual Alain Delon.

The third, THE LAST TRAIN (1973) takes us back to Occupation days, where Granier-Deferre is miraculously able to coalesce the horrors and chaos of war, the recklessness of fraught decision-making by noir characters, and an exalted, impossible romance to make a film that straddles the gulf between the lost world it portrays and the “old style” of French filmmaking that had become anathema. Finely wrought performances from the central characters (Jean-Louis Trintignant and Romy Schneider) make THE LAST TRAIN a heart-pounding cinematic experience and a fascinating collision of filmmaking precepts.

SO, if my count is correct, we’ve covered eleven of the fifteen films. What else is there? Well, there’s Jean Gabin. Of course: every FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT has Gabin in it; we’d be drummed out of our own union if we failed to do that! For FRENCH ‘22 we present Gabin as possibly the most bedraggled anti-hero in his entire pantheon of such characters, Pierre Arrignon, clinging to the wreckage of life as he attempts to escape a star-crossed past, in a film named, justly, for its fixation on obstacles: THE WALLS OF MALAPAGA (1949).

The French-Italian production helmed by René Clément has suffered in its reputation since its original veneration (awards at Cannes and in Hollywood), as some have come to see it as rehash of Gabin’s 30s films. Much of this is lazy thinking, however, based in large part on a spurious connection between quality and box office success; having seen the film recently, and comparing Gabin’s work here to the approaches he employed in later films such as DES GENS SANS IMPORTANCE, we’re happy to vouch for him—and for the two Italian actresses playing opposite him, Isa Miranda (as his embattled love interest) and Vera Talchi (a vibrant, unique performance as Miranda’s teen-age daughter).

The oft-maligned “hatchet man” of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther, extolled this film as being suffused with “feeling for human beings caught in the undertow of life.” We would be wise to follow Crowther’s line of thinking regarding the stark but elegiac tone of neo-realist film and much of the forgotten French film noir of the late 40s to see how a particular mood and modality enters into filmmaking at this moment: by doing so, we’ll possess a more fully-formed understanding of the great “aesthetic breath” of Europe in the aftermath of its calamity and the poignant, despairing wisdom it can still provide to us.

Then there is the man you love to hate—love and hated passionately (and simultaneously!) by European audiences during his long, peregrinating exile from the director’s chair: Erich von Stroheim. He is the haunted Professor Hoffman in Edmond T. Greville’s MENACES aka THREATS (1940), the hidden-away boarder in a Paris hotel as the German offensive against France heats up. Paired with LA DIABLE SOUFFLE, the film demonstrates Greville’s mastery of claustrophobia and dread, reminding us that every human being has a dark side.

MENACES is also highly focused anti-Nazi propaganda, and it is yet another of von Stroheim’s films that was brutally tampered with once the Germans stormed into Paris. We could almost make a fully-fledged FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT using just von Stroheim films…but an actor with such extremes of intensity and a penchant for similarly haunted roles is best doled out more sparingly: be assured that he’s at the top of his game here.

The alluring Françoise Arnoul (1931-2021), like so many French beauties of the fifties, is undervalued because of the incessant focus on her looks. Most recently FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT audiences were shown proof of her superb thespian skills in her work opposite Jean Gabin (the previously mentioned DES GENS SANS IMPORTANCE), but she has been a fixture in these festivals since nearly the beginning. We look forward to the audience’s reaction to her as she plays a resistance fighter in LA CHATTE (1958), Henri Decoin’s taut, oddly premonitory film (re-watching Melville’s ARMY OF SHADOWS after seeing LA CHATTE will make this notion clearer). Arnoul dials her sensuality up to ten in service of a story that occasionally threatens to fall apart, but her labors were rewarded: despite her demise at the end of the film, LA CHATTE proved so popular that they made a sequel anyway.

Finally, there is HEAD AGAINST THE WALL (1959), which will permit those who viewed the early films of Jean-Pierre Mocky (earlier this year in our MIDCENTURY MADNESS series) to get a sense of him as actor. The film, originally slated to be Mocky’s debut as a director, was ultimately directed by Georges Franju, who adds his astringent poetry to a harrowing tale of mental hospitals and patients at the mercy of those who run them.

Franju and the great cinematographer Eugen Shufftan eschew violent action and the now-clichéd imagery of later films like SHOCK CORRIDOR, but the dread and alienation becomes palpable as the action unfolds. We watch Francois (Mocky), locked up by his father for being a troublemaker, make friends with a meek epileptic (played with great sensitivity by Charles Aznavour, in his film debut). As they have their fill of the macabre atmosphere of their prison and the impasse in treatment approach embodied by the hospital’s lead doctors (Pierre Brasseur and Paul Meurisse), the two cook up an ill-fated escape scheme, and there are consequences. Meanwhile, Francois’ off-and-on love interest Stephanie (Anouk Aimee), does what she can to extricate him from his predicament.

We think viewers will find that HEAD AGAINST THE WALL plays especially well after GOUPI MAINS ROUGES, a double bill more than willing to insinuate that “madness runs in the family.”

IS this the “best” FRENCH HAD A NAME FOR IT? It’s both a silly and an obligatory question in the odd, quasi-pandemic world in which we live, which is its own form of a “noir universe.” We’ve had variable approaches—sexy thrillers (#1 and #2); our initial Hossein showcase and an expanded sense of the French noir timeline (#3); eclectic anthologies (#4, #5 1/2, and FRENCH 21); surveys of decades (#5, #6). FRENCH ‘22 settles in closest to the anthologies, and it really demonstrates that the noir-inflected films in the still-shunned “cinema de papa” period have a greater weight and resonance than anyone is willing to admit.

One must acknowledge that after eight years, it sometimes feels that we are beating our own “head against the wall,” but we’re very grateful for the warm response of those who’ve attended our efforts since 2014 and we look forward to seeing the most faithful of you in November. (A schedule that corrects some typos in our earlier email blast through our web site is attached here, along with the PayPal link for those who wish to purchase an all-festival pass: all fifteen films for $75. Note that passes must be purchased on-line with this link, there are no sales at the Roxie box office. Passes can be picked up at the Roxie box office with proof of purchase beginning Saturday, September 24.)