PERMIT me one more shout-out to Elliot Lavine, one of the truly great film programmers, who has been my inspiration (if not exactly my role model!) for the series that Midcentury Productions has undertaken since 2014. Elliot’s skill at putting together a double bill remains unparalleled, and is always in my mind when I set out to follow in his footsteps.

And a series such as FRANCO-AMERICAN NOIR, where we get to collide two national cinemas’ competing visions of that nebulous entity known as “film noir,” is a perfect place to follow the Lavinean model. If I could boil it down (I really can’t, but I’ll do so anyway…) the process works like this: find extremity, add poetry, then let the texture tease itself out as the viewer digests the correspondences and contrasts in each film.

So, for our Saturday matinee this August 12th, we’re doing just that. This is a double bill that recaptures the sublime anarchy of Elliot’s approach to American “B”-noir, but with a Gallic twist of gothic proportions. I hope that readers who’ve been away from our shows since the pandemic for whatever sets of reasons (and there are so many…) will be galvanized by this post to join us at the 4-Star Theater for this utterly unique excursion into the depths of feminine bravado.

MAKE that desperate bravado, by the way—an adjective-noun combination that is saturated in every frame of DECOY (1946), director Jack Bernhard’s all-out ploy to make his new wife, British actress Jean Gillie, into an infamous overnight sensation in America.

It didn’t work—and Bernhard & Gillie would cash in their marital chips soon after the film, roaring from the bowels of Monogram Studios (which put far more $$ behind ice skating queen Belita), found its way onto the ash heap. Fifty-odd years later, however, DECOY resurfaced and became an instant sensation, primarily because of the unrepentant cunning and ultra-supercilious disdain on display by Gillie’s character, the uber-bitch Margot Shelby.

Screened twice by Eddie Muller in the early, pre-TCM era of Noir City, DECOY disappeared from the noir festival rotation almost as quickly as it had arrived—including being omitted from Muller’s 2022 update of Dark City, his 1998 survey of the “lost world” of film noir. There may be good reasons why it became so scarce—it was briefly available as part of the Warner Archives’ now-defunct streaming service—but its prolonged absence still remains a puzzle. (To his credit, Muller at last screened DECOY last December on TCM’s Noir Alley.)

WHICH is why we’re getting it back onto the big screen on August 12th—films like this especially need to be seen by an audience, so that the audacious extremity on display can percolate through the crowd and create the type of murmur that Elliot Lavine was always in search of when putting his programs together.

If you’re waiting for me to give you any sense of what happens in DECOY, you’ll be waiting a long time. Believe me, it’s all for the best that you come to the theater completely unprepared for what you’ll see—but I assure you that you will agree that Jean Gillie creates the most repellently alluring, seductively lethal, cold-as-an-ice-floe, breathtakingly bitchy femme fatales in all of American noir. Both Gillie and her character literally come from out of nowhere, and lead us into a delirious hell, with men falling over like drunken bowling pins at regular intervals.

AND both Margot—and Gillie—disappear in blaze of malevolent, tragic glory. After the film flopped, Gillie split with Bernhard and returned to England, having appeared in only one other Hollywood film—a small role in Hungarian ex-pat (by way of the UK) Zoltan Korda’s THE MACOMBER AFFAIR (1947). Whereupon she contracted pneumonia, and abruptly died in 1949 at the age of just 33.

This is a film that every “standard-issue” film noir fan needs to see in a theater.

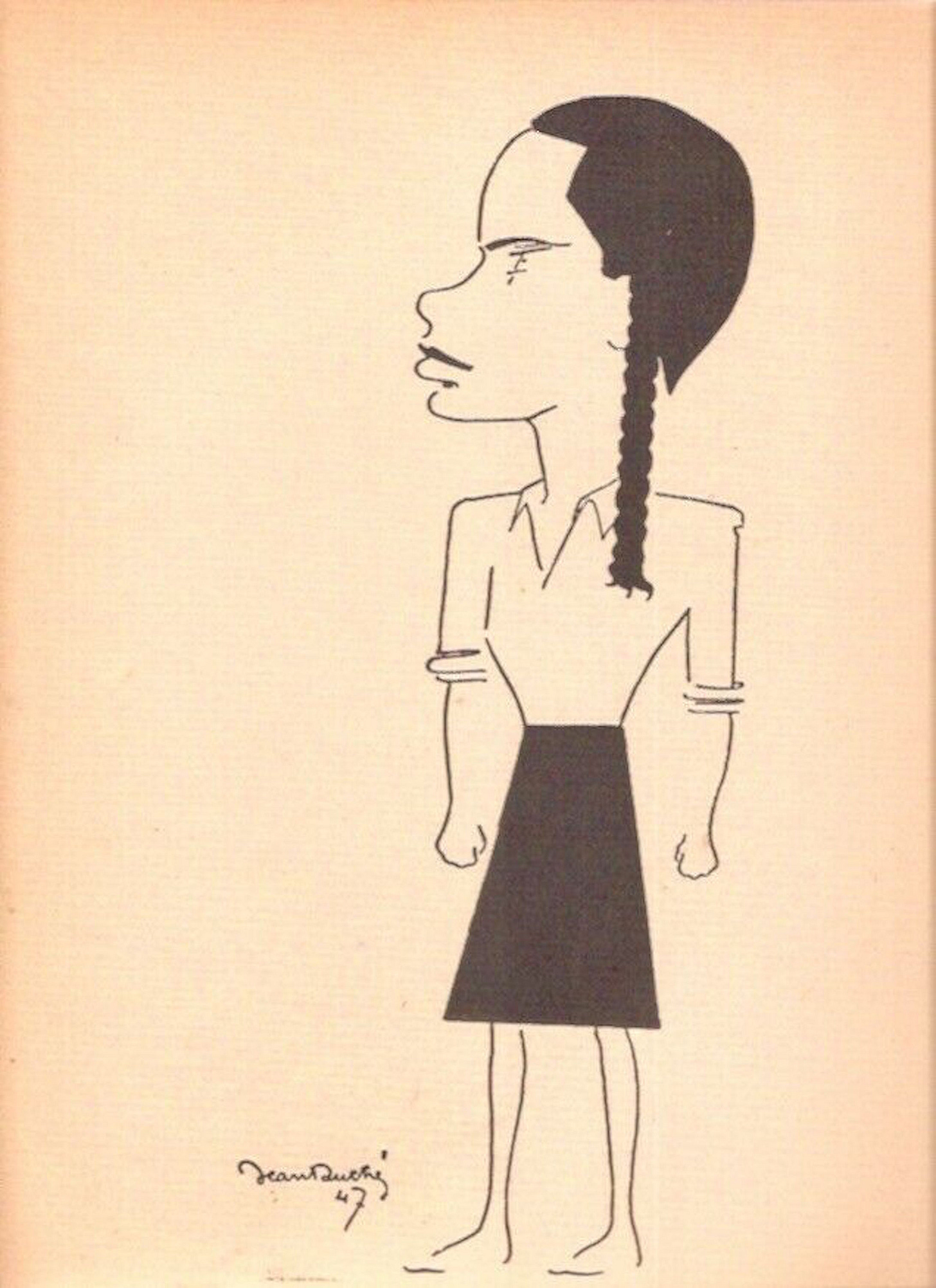

THAT said, it’s even more important that you become aware of the exceptional French actress Andrée Clément, whose brief, embattled life I chronicled in 2018 when we screened two of her films—including THE DEVIL’s DAUGHTER aka LA FILLE DU DIABLE (1946, France, Henri Decoin).

Like Ann Savage in DETOUR, Clément does not enter the film (even though it’s named for her character!) until a bit more than halfway through its running time. But she makes up for that with a performance that embodies all of the nuances that alienation has to offer (and film noir really is about alienation: the modern state of soul-sickness due to the drift of a world away from anything other than cynical lip-service to humanism).

After Saget the escaped criminal (Pierre Fresnay, best known to noir fans as the intrepid doctor in Clouzot’s LE CORBEAU) has landed in a small town and met his match in the village doctor (Fernand Ledoux), who knows who he is and blackmails him on behalf of the community for his robbery loot.

Then he is introduced to a scrawny teen-aged girl with a knowing glint in her eye.

THIS is Isabelle, whose father had been ostracized by his neighbors in the village for unproven criminal allegations and had taken his own life. This event turned Isabelle into a teen-aged criminal mastermind, hell-bent for revenge against her community.

DECOY never gets past greed as the motivation for Margot Shelby’s actions; THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER gives Isabelle a nuanced, complex backstory that plays perfectly into a plot twist so astonishing that it even takes Pierre Fresnay’s character completely by surprise.

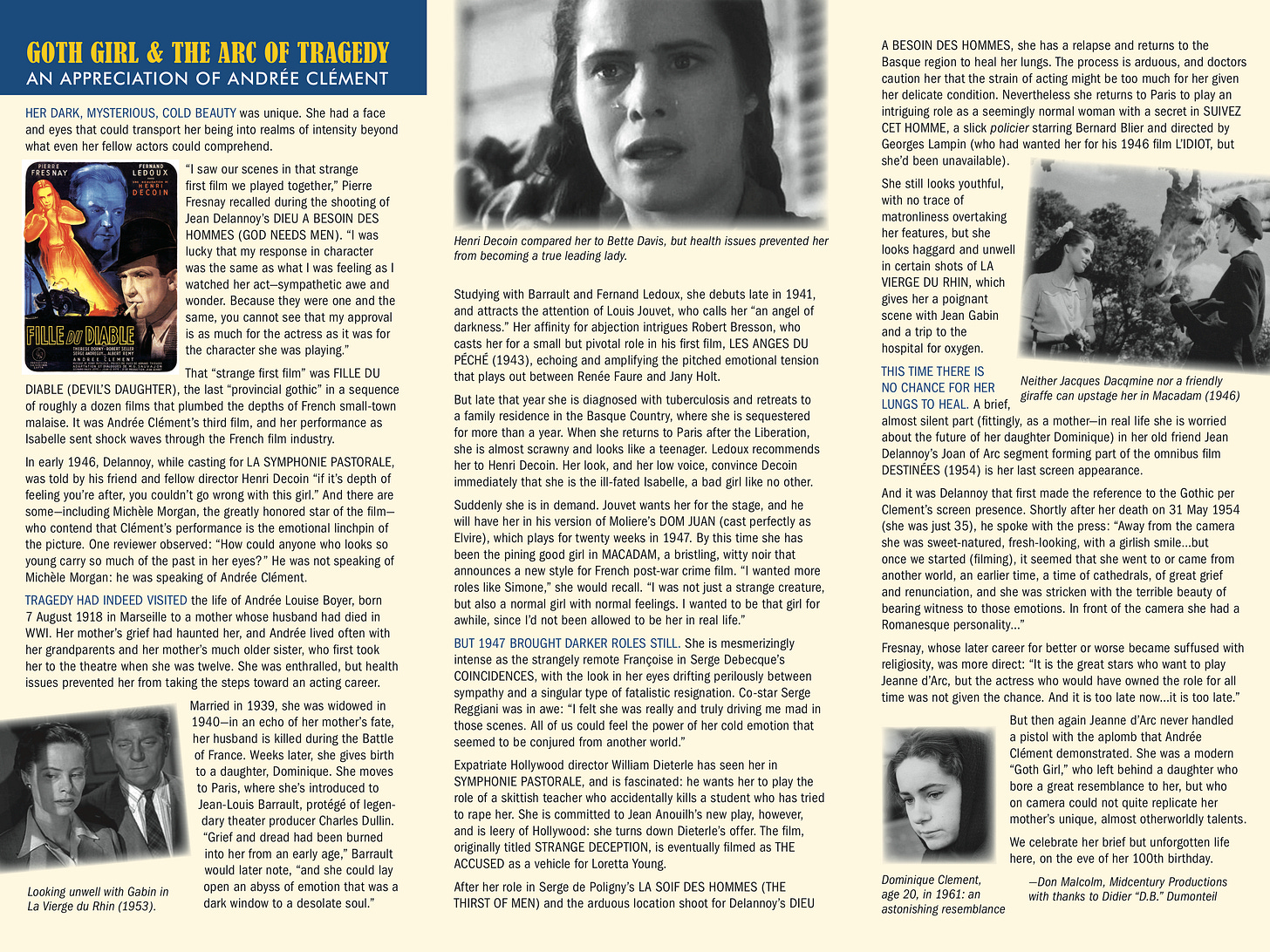

Clement’s look in this film is what one could call “goth-anorexic,” but her eyes are haunting and beautiful, even as they register infinite scorn. Her character and its issues with the small-town hypocrisy that destroys her family is the “gothic twist” in what seems to be a gangster-on-the-run tale, and brings THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER firmly into the “provincial gothic” sub-class of French film noir that was invented and flourished during the Occupation period. This sub-type lingered on into the post-WWII years, trickling out a series of astonishing films, many of them directed by Henri Decoin—who also masterminded the “madness in small town” noir NON-COUPABLE aka NOT GUILTY (1947), which features a towering performance from the great monstre sacré Michel Simon.

THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER brought Clément great acclaim, with interest extending all the way to Hollywood. William Dieterle, working at Paramount, wanted her to play the lead role in a film entitled STRANGE DECEPTION, where she is a teacher who undergoes a starling transformation when she is sexually assaulted by one of her students. But like her character in THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER, Clément was tubercular, and her health flickered, forcing her back to her family home in the Basque country. (She was leery of Hollywood anyway.) The film was eventually made as THE ACCUSED (1949), and became a vehicle for Loretta Young.

THE DEVIL’S DAUGHTER uses nuance and surprise—the poetry of noir—to present a character whose enmity and extremity are embedded in her backstory. We can’t really say that about DECOY, and therein lies one major aspect of “la différence” between French noir and its American counterpart. That’s what we want you to experience on Saturday afternoon, August 12th at the 4-Star. You’ll recoil with pleasure at Jean Gillie, but you may also follow me in my swoony. semi-dysfunctional empathy and become hopelessly smitten with Andrée Clément.

Worse things can happen to you, believe me!