Colette, Louise, Annette, Solange...

PHOEBE GREEN ON THE HIDDEN WOMEN OF THE "CINEMA DE PAPA"...

IT is now approaching six weeks before “Auteures” (aka THE OTHER SIDE OF THE LOST CONTINENT ‘24) will begin screening at the Roxie Theater (March 30-April 3, fifteen films). All-festival passes go on sale March 4, and between now and then we will provide periodic previews of the films in the series. I’m most pleased to kick that off with a superb overall introduction, which is mostly the work of esteemed colleague Phoebe Green.

She is the mastermind behind “Auteures,” a vibrant, highly varied follow-up to our look at the “other lost world” of classic French cinema that played the Roxie last spring. And, as you’ll soon see, she has much to tell us: take it away, Phoebe!

A FARANDOLE OF FEMMES!

MCP’s “Auteures” festival (fifteen films from March 30 to April 3) celebrates women as characters—and, crucially, as creators—in the predominantly masculine world of classic French cinema.

We were hoping to avoid a “he said, she said” – but realized that we had two different ideas of what makes an auteure[1]. Is it her art, regardless of her perspective on feminist philosophy or the female role in the society in which she lives and works? Or is it her agency in addressing distinctly female issues? Both perspectives are showcased in an eye-opening weekend.

These novelists, screenwriters, directors and “feminist stars” (before that term exploded into common usage) have been as rarely screened in the US as so many of the French noirs that have become MCP’s calling card. With “Auteures,” we bring these exceptional works and women back into view...

The matrix of interconnections among these women evokes the farandole: a serpentine of dancers, hand in hand, twining giddily through a festive space.

And there are a few men whose mentorship and advocacy for our “auteures” will reveal itself throughout the series. As we’ll see, however, these women—from Marie Epstein to Jeanne Moreau—were more than capable of dancing on their own. Let’s meet them now…

BY the time World War II ended, Colette was over seventy and forced to retreat almost entirely to her bed, the fur-coverleted “raft” overlooking the gardens of the Palais Royal by day and illuminated by the blue lantern of her lamp, shaded with her favorite writing paper, by night. She had cut through the gloom of the Occupation with a nostalgic novella of the Belle Epoque, Gigi, where an adolescent brought up to become a courtesan achieves an unexpected happy ending.

A young woman, Jacqueline Audry, fresh from her first experiences as a director, begged permission to film it: “I will not disappoint you.” Gigi (1949) made that young woman a bankable director and her equally young and untried leading lady, Danièle Delorme, a star.

Its success also raised a mini-wave of Colette adaptations, including two others featuring the Audry-Delorme team. Chéri (1950), about a courtesan at the end rather than the beginning of her career, was not one of them, but its skillful adaptation and screenplay were by Audry’s husband and collaborator, Pierre Laroche, as was also the case for the Delorme-starring Minne (1950). Le blé en herbe would be brought to the screen by Claude Autant-Lara in 1954, but a decade earlier Marc Allégret had wanted to film it with Danièle Delorme and Gérard Philipe.

Another relevant tidbit about Marc Allégret: it was he who suggested to a bright 14-year-old working in a bookstore that there was a place for her in filmmaking. That young girl was Léa France Gourdji, later known as Françoise Giroud, writer, editor, and (eventually) politician. She began as script girl on films by Allégret, Jean Renoir, and others (including the Colette-scripted Lac aux dames) and moved on to screenwriting and co-directing. One of her first scripts was Antoine et Antoinette, a neorealist-tinged drama of a lottery ticket lost and found, for Jacques Becker, in the midst of a remarkable group of films about post-WWII French youth.

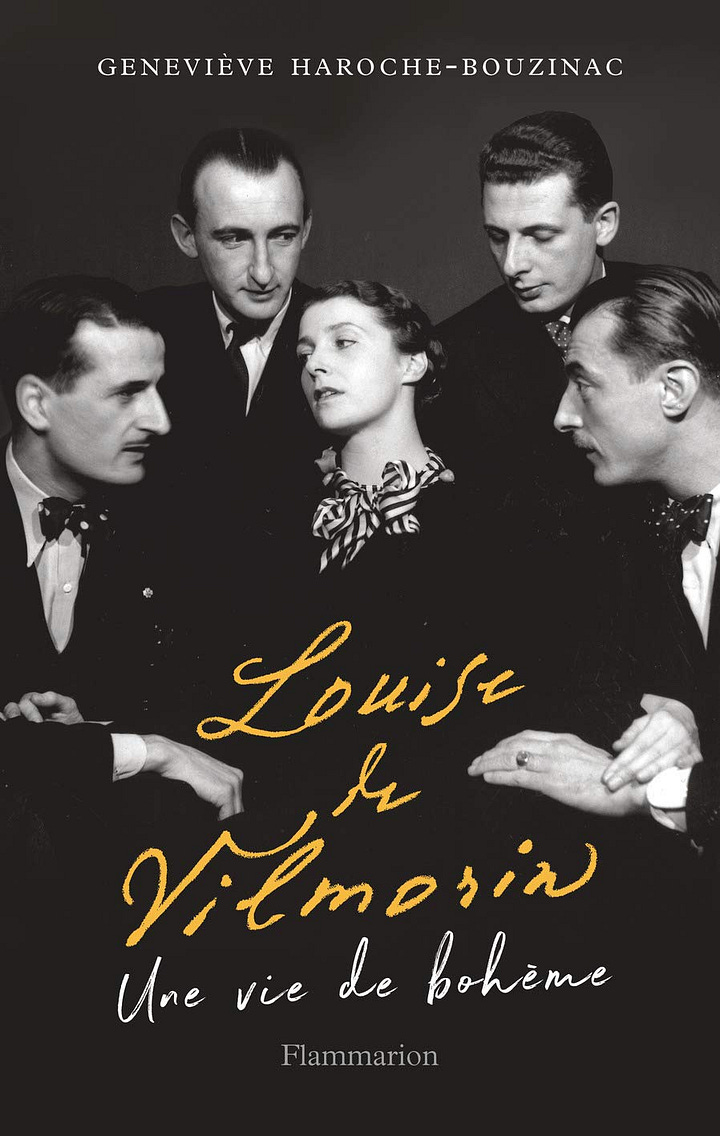

Antoine et Antoinette stemmed from an initial idea by Louise de Vilmorin, an eccentric beauty and wit who enchanted Saint-Exupéry, André Malraux and Orson Welles, among others—Jean Cocteau wanted to marry her, c’est tout dire.

In this phase of his career, Becker clearly valued female collaboration: his two films written by his then-lover Annette Wademant, the well-known Edouard et Caroline and the even lovelier Rue de l’Estrapade, were a virtual mind-meld not only between director and writer but with the lead actress, Anne Vernon, whose life was woven into the scripts and who remained Wademant’s lifelong friend. Max Ophuls, impressed by Wademant’s “woman’s touch,” invited her to co-write his celebrated adaptation of Louise de Vilmorin’s novella, Madame de…

EVEN more de Vilmorin will reveal itself in short order, but on Sunday evening the series moves back in time (the 1930s) to capture another theme that these “auteure-ist” films will explore: the opposing visions of a woman’s place in the world. La Maternelle, with keen oversight from writer/co-director Marie Epstein, brings that issue into sharp focus nearly two decades before it emerged in the pioneering feminist writings of Simone de Beauvoir. (Epstein and de Beauvoir’s message is, sadly, not quite absorbed in the mid-50s film L’Amour d’une femme, where Micheline Presle is pressed to give up a career that she is clearly more than qualified to pursue.)

Jeanne Moreau is one of those screen actors distinctive enough to stand as auteurs in their own right. On Monday April 1st, she is featured in a triple bill: first, Les Amants, Louise de Vilmorin’s variation on an 18th-century pavane of formalized sexual intrigue. It’s followed by Orson Welles’s The Immortal Story, adapted from the work of de Vilmorin’s Danish sister-spirit, Karen Blixen (better known as Isak Dinesen). And finally, in keeping with MCP’s relentless archeological calling, things conclude with a rare treat: Moreau’s very first screen appearance, aged 21, in Dernier Amour, scripted by Françoise Giroud.

On Tuesday the 2nd, the focus shifts to a fizzy (in French: pétillante) double bill of screwball romances: L’honorable Catherine, written by Solange Térac (also the screenwriter for Ombre et lumière, showcased in MCP’s proof-of-principle Other Side mini-series in 2019). Térac was a mercurial, galvanizing presence in this shadowy world of the “auteures”: in the early 30s, as Solange Bussi, she was the director of an adaptation of Colette’s La vagabonde. (Her life and career await the ideal biographer…)

We reunite with Marc Allegret for our second comedy, where Jeanne Moreau is embroiled with Dany Robin and Jean Marais in Julietta, another Louise de Vilmorin novel that was (again) adapted by Françoise Giroud. The complications in finding a truly fulfilling love, so often sent up in the screwball genre, dart and dash delightfully upon themselves (in something akin to a farandole) as we watch, hoping against hope that our headstrong heroines will somehow manage to prevail...

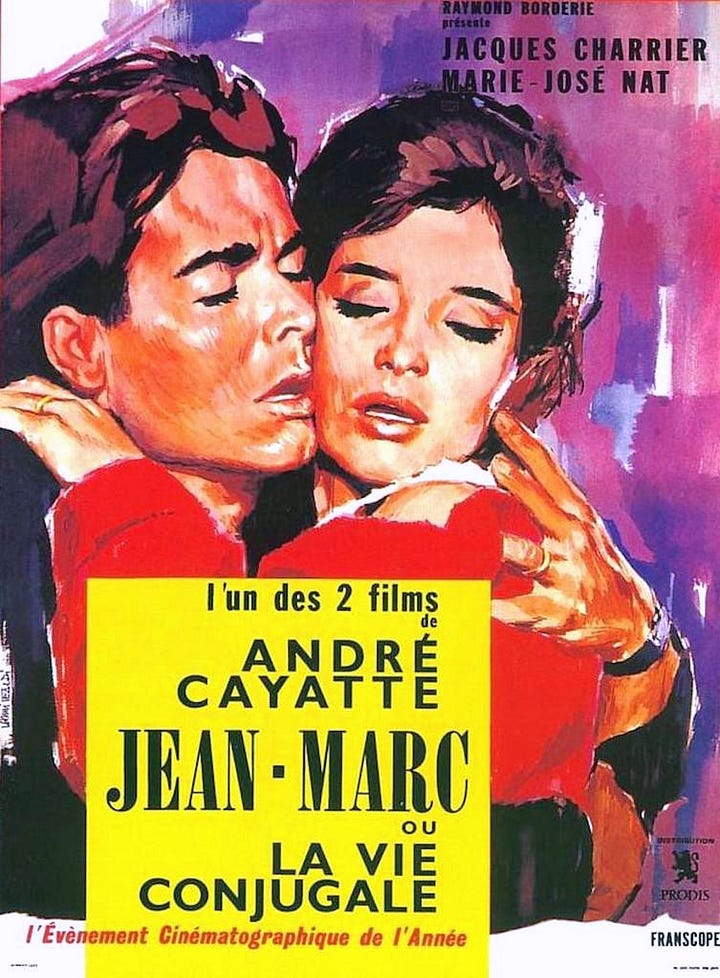

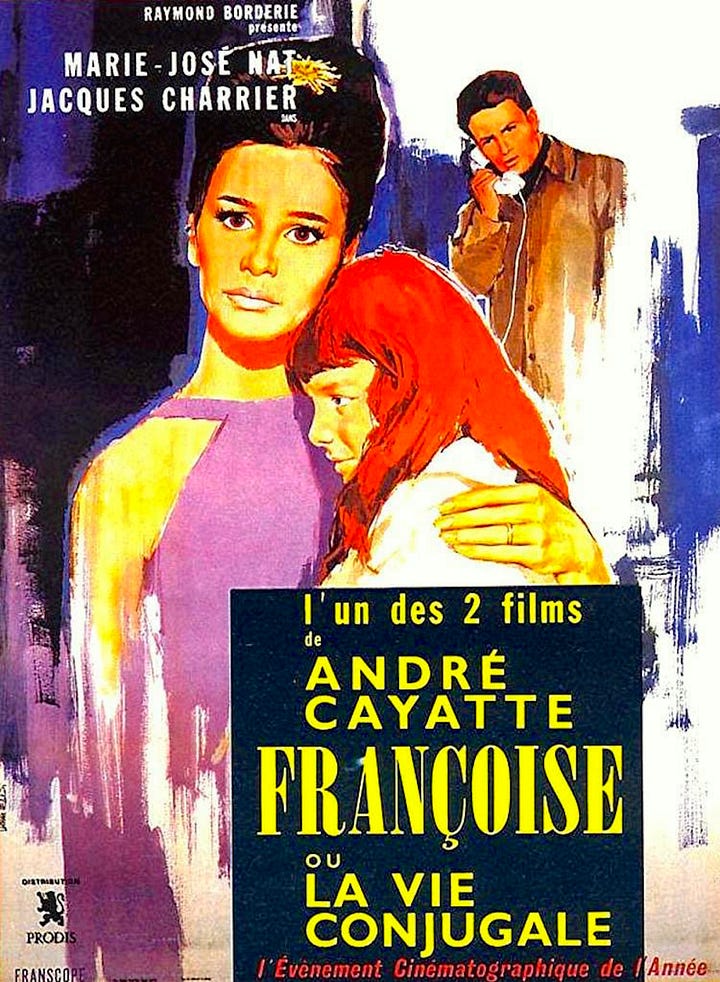

Things become more serious on closing night, as La vie conjugale—André Cayatte’s long-lost double-barreled look at “marriage, French style”—receives its first American screening in six decades. Don Malcolm has already teased this unique double feature, which shows us the salient events in a marriage from the very different vantage points of husband (Jacques Charrier) and wife (Marie-José Nat). It is a masterful but sobering reminder that women’s issues remain thorny and difficult; even sixty years after its release, we will part from the closing salvo in this series knowing that for women to be in charge of their destinies in the 21st century—to truly be “auteures”—there is still much to be done.

[1] To the dismay of the Académie Française, écriture inclusive has created feminine equivalents for auteur: auteure and autrice. We couldn’t resist!